Dr. C.M. Johnston's Project

Discover McMaster's World War II Honour Roll

Byron N. F. Rawson

Before World War II ended, Byron (Barney) Rawson, in his twenty-third year, was being hailed as the “youngest Wing Commander in the British Empire”. His rise in the RCAF had been in a word, meteoric. In the brief span of three turbulent years he had received promotion after promotion, been awarded the DFC and bar, and ended up serving as commander of the Pathfinder Wing in 8 Group, which formed part of Bomber Command, the RAF's principal offensive weapon.

Before World War II ended, Byron (Barney) Rawson, in his twenty-third year, was being hailed as the “youngest Wing Commander in the British Empire”. His rise in the RCAF had been in a word, meteoric. In the brief span of three turbulent years he had received promotion after promotion, been awarded the DFC and bar, and ended up serving as commander of the Pathfinder Wing in 8 Group, which formed part of Bomber Command, the RAF's principal offensive weapon.

Barney Rawson's short, poignant, and action-packed life had begun on 3 December 1922 in the small community of Smooth Rock Falls in northern Ontario, where his father, Norman, was pastor of the local Methodist Church. His English-born mother, Mazie Maud (Sexton) Rawson, had already provided him with two sisters, Helen and Elizabeth, and would give birth to another, Norma, six years after Barney's arrival on the scene. The family subsequently moved to Ottawa where the Rev. Rawson assumed a new pastorate and enrolled his children in that city's school system.

For his part, Barney started his educational career at the Mutchmor and McHugh Public School (now hived into two) in the capital's attractive Glebe district where the family resided. From there he proceeded in 1935 to Glebe Collegiate Institute, one of the many new high schools opened in the early ‘twenties to meet the needs of Ontario's growing adolescent population. Since very little was recorded of junior classmen in the school's yearbook, Vox Glebana, nothing is known of Barney's extracurricular activities, if any.

All that would change in 1937 when the Rawson family moved to Hamilton and he enrolled at Westdale Collegiate Institute (WCI). His father had been appointed to the prestigious pulpit of Centenary United Church, the venerable place of worship in the heart of the city's downtown. He settled his family in the manse provided on fashionable Robinson Street. While the Rev. Rawson launched what soon proved a charismatic pastorate at Centenary, young Barney entered into a busy round of activities at WCI, where he would complete the matriculation work he had begun in Ottawa.

Along with new found-friend and classmate, William (Bill) McKeon [HR], the tall and lanky Barney went out for track and field, joined the school's rifle team, and was elected to the Triune Society, the student governing body that, among other things, arranged debates, organized social functions, and put on school plays. The popular Barney also contributed his thoughts to WCI's yearbook, Le Raconteur. For its 1940 issue he wrote a facetiously pointed article, “Things Needed Around Westdale”. He lightheartedly lamented the absence of a hockey rink and a camera club, which as an avid photographer he would have readily joined.

What tongue-in- cheek Barney really set his sights on was the elimination of the stag line at school dances:

… You know … in the opinion of a great many … Tea Dance goers, the stag line is a nuisance and a menace. You just get started on a dreamy dance with the dreamy-eyed girl of your dreams, and somebody taps you oh! so politely on the shoulder, and says so sweetly—“May I cut in?”

When Barney was not attending tea dances and otherwise courting diversions, he paid the requisite attention to his studies. He had little difficulty meeting the academic challenge, graduating with his senior matriculation in the spring of 1940.

He subsequently enrolled, as did fellow student Bill McKeon, at nearby McMaster University, a former Toronto institution which had just marked its tenth year in Hamilton. He registered in Honour History (Course 22) and indicated his intention to become not a man of the cloth like his father but rather a lawyer, perhaps even a politician. But during the session he spent at McMaster the renewal of war with Germany in September, 1939 was very much on everyone's mind, not least Barney's. It was also a serious concern for his father, a veteran of the Great War (World War I), the war that was supposed to end all wars. He had started off as a foot soldier and returned home a captain, a title by which he was often addressed in the secular world in which he frequently moved.

The war situation had only become more precarious in the summer before Barney registered at the University. France and the Low Countries had been speedily overrun by the German Wehrmacht and Britain had been all but invaded, the only things standing in the way, a heavily taxed Royal Navy and the RAF's embattled Fighter Command. The latter's acclaimed though narrow triumph over the Luftwaffe in that fateful summer of 1940 undoubtedly helped to inspire Barney's forthcoming enlistment. All the same, he resolved in the short term to engage as much as possible in McMaster's extracurricular world and to that end ventured out for freshman football and track and field and took as well to the badminton and tennis courts. But then, starting in January, 1941 – another reminder of the worsening war situation overseas -- these athletic activities had to share time with his required training in the McMaster Contingent of the Canadian Officers' Training Corps (COTC), a unit established at the outbreak of the conflict.

Meanwhile on the academic side, Barney indicated on a questionnaire that he had little difficulty linking lecture material with his required reading though he confessed to being a “crammer” for examinations. His faculty advisor, Professor Norman MacDonald of the History Department, added his own assessment. He concluded unhappily that while Barney was a “serious seeker after truth”, he had difficulty “concentrating … was easily diverted”, and like a good many freshmen found the “transition to university bewildering”. Bewildered or not, easily diverted or not, Barney finished out his academic year on a high note, indeed achieving a first in his history course and clearly qualifying for the second year of his program.

This, however, he declined to do. He had already made up his mind to join the RCAF and he wasted little time informing his family of the decision. He also made his intentions known to the McMaster Registrar, Elven Bengough, who on 16 May confirmed Barney's standing at the University in a communication to an Air Force official who had requested it. The moved Bengough wished Barney well, adding in a characteristic flourish that “Alma Mater … salutes you”. In turn the McMaster COTC, on learning of his decision, sensibly struck him off strength and excused him from its customary summer camp training at Niagara-on-the-Lake.

On 19 May, during an interview with another RCAF official, Barney obviously made a good impression. He was judged to be “confident, alert, quick, athletic, clear [of speech], and sincere”, in effect, a “fine type of Canadian lad” who should do well as a trainee and end up an officer and in all likelihood a pilot, a keenly prophetic statement as events proved. Meanwhile, not only was Barney's deportment taken into account but his “dress” as well, which was approvingly described as “neat, conservative, and clean”. Patently conservative attire was taken for granted by the RCAF because its opposite – flamboyant? – was not even provided for on the interview report sheet, only the word “careless”.

A week after his productive interview, Barney formally enlisted in the RCAF and was posted to No. 4 Auxiliary Manning Depot at St. Hubert in Quebec, the province where he would take much of his training. At St. Hubert, like other green recruits, he was introduced to the workings of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), the Anglo-Canadian arrangement for training combat air crews in the comparative safety of the Dominion. He spent some two months at the manning depot, an interlude relieved by at least one 36-hour leave to visit family and friends in Hamilton. At St, Hubert he was engaged for the most part in musketry and marching drills designed to instill the proper “airmanship” in new recruits.

That achieved, Barney was then sent to nearby Montreal and to temporary guard duty at No. 12 Equipment Depot, a duty routinely assigned to allow time for the next instructional level to be cleared for a fresh intake of trainees. A month of marking-time passed in Montreal, made palatable by pleasant leaves in that diversion-filled metropolis. A social highlight was a visit he paid with a boyhood friend and fellow trainee, Gordon (Gord) McClatchie, to the mansion of Senator Lorne Campbell Webster, an acquaintance of Barney's father. A coal tycoon and financier, the Senator laid on some lavish hospitality for the two impressed and grateful servicemen.

Barney's next training stage was one that always proved a pivotal turning point in a would-be airman's career. On 21 August he was dispatched to No. 3 Initial Training School (ITS) at Victoriaville, where he and others in his group, Gord McClatchlie included, were put through a screening process to determine who should train as pilots -- ordinarily the most coveted trade -- navigators, or wireless operator/air gunners, the principal components of air crews. Having his heart set on handling the controls of an aircraft – as his interviewer had indicated that he should -- Barney was pleased to be chosen for flight instruction and to be posted accordingly to No. 4 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) at Windsor Mills. At this station, where he arrived on 26 September, instruction was mostly carried out on th e Fleet Finch biplane, a trainer which Barney in due course succeeded in mastering.

That crucial requirement met, he moved on in late November to the next stage, more specialized instruction at No. 9 Service Flying Training School (SFTS), based at Summerside in scenic Prince Edward Island (PEI). It was Barney's first visit to the Maritimes and the Atlantic shore, soon to be assailed by fierce winter storms. It was also his first encounter with the advanced and powerful single-engined trainer, the North American Harvard. Barney soloed successfully in the aircraft on 15 December and once again met the flying challenge. As anticipated, he passed with high grades, standing seventh in his class and qualifying for a commission. So did his friend, Gord, who was not far behind him.

On 10 April 1942, at a ceremony on the Summerside station, the two airmen received their wings, were routinely promoted Temporary Sergeants, and then almost immediately appointed Pilot Officers. For Barney it turned out to be the first rung on the ladder to the many promotions and appointments awarded during the course of his service, the overseas stage of which was about to begin. Indeed, without further ado, he was one of several in his group immediately tagged for an ocean voyage to the air war. Friend Gord, who would ultimately fly Mosquito fighter bombers, left on a later one and their paths never crossed in Britain.

On 1 May, following his posting to the RCAF's 1 Y Depot in Halifax, the usual jumping off point for a wartime Atlantic crossing, Barney embarked in a convoy bound for England. After his safe and speedy arrival on 7 May he was assigned to what was called the RAF Trainees Pool. Within a week he was dispatched along with other newly landed airmen to the Personnel Reception Centre in Bournemouth, the peacetime resort city on the English Channel. While there he was on the receiving end of lectures, medical inspections, and, among others, high altitude tests. The latter he presumably passed, otherwise he would not have been assigned, as he later was, to heavy bombers, which ordinarily operated at a considerable height.

Before leaving Bournemouth in late June, Barney was fitted out with battle dress and flying kit and instructed to report to No. 6 Advanced (Pilots) Flying Unit (AFU), based at Little Rissington in Oxfordshire. Built as an SFTS in prewar days on a picturesque Cotswold plateau, it had only recently been converted to an AFU. It was designed primarily -- as a station history puts it -- to “hone” newly arrived pilots like Barney for the complexities of the “Bomber War” planned against Germany. Its first devastating phase had opened with the 1000-plane raid against Cologne just a month before Barney arrived at Little Rissington.

He was shortly given an opportunity to sharpen his flying skills and learn more about bombing tactics on the Airspeed Oxford as well as on the Avro Anson, another veteran trainer. While at Little Rissington he used some of his spare time writing home to family and friends, though he had to disguise his whereabouts as “Somewhere in England”, the mandatory wartime custom. On 17 August, in a letter to Gord McClatchie, then stationed at Trenton, he pronounced the English food and life overseas good all in all, in spite of there being a war on. He had both favourable and harsh words for the Airspeed Oxford: “a nice kite in the air but a bastard to land”. The recurring fog and mist, a British weather staple, often “obliterated the horizon”, making night flying difficult if not at times hazardous. He half-jokingly cited other potential perils. One night, for example, while his unit was on a cross-country exercise a German heavy bomber, “a Dor[nier] 217”, joined their “circuit”, the upshot of which was not recorded in the letter. The incident, Barney added, occurred at a time when “so many planes of both sides were in the air you really had to keep your eyes peeled”.

As for his future as an operational pilot, he confided to his friend that he hoped to be assigned to Bristol Beaufighters or Mosquito fighter-bombers, both twin-engined low low-level attack aircraft endowed with formidable speed and firepower. “I hope to hell”, he feelingly remarked, “I get one or the other”.

He ultimately got neither and had to resign himself to flying a “Wimpey”, that is, a Vickers Wellington bomber, named after the Popeye cartoon character, J. Wellington Wimpey. His letter's only genuinely sour note was struck when he wrote about the young woman he had been dating at home. It appears that she “suddenly” stopped writing when she learned that he was “definitely overseas”, a decision that “doesn't leave a very pleasant … memory of home ….”.

On the flying front, however, it was a different story and the reinforced instruction produced the desired results. After two months at the AFU Barney was posted on 1 September to a potentially front-line base, RAF Wellesbourne Mountford in Warwickshire, home of No. 22 Operational Training Unit (O T U). Shortly after Barney's arrival, given the number of RCAF personnel on the premises, the unit was “Canadianized”, that is, put under Canadian leadership, part of a process that would lead shortly to the creation of 6 Group, the RCAF formation in Bomber Command, to which Barney in due course would be attached. Wellesbourne airfield, located in Shakespeare country barely six miles from Stratford-upon-Avon, had been speedily built in 1941 atop extensive farmland urgently requisitioned by the government. Before Barney appeared on the scene, Wellesbourne-based aircraft of 22 O T U had already participated in the recently launched Bomber War, including the vanguard assault on Cologne. The crews, however, made up of instructors and the more seasoned students, often suffered heavy casualties in these dangerous on-the-job training exercises.

As it turned out, Barney for his part was not scheduled for any fully operational missions during his stay at Wellesbourne. He took part instead in a lengthy series of cross country flights and night flying exercises as well as a number of mock bombing runs, principally over the Thames Estuary. He performed all these varied tasks, as he expected he might, on 22 O T U's mainstay twin-engined “Wimpeys”, one of which, his parents were elatedly told on 24 September, he had just commanded for the first time as a pilot. All the same, some three weeks later Barney wrote his friend Gord that he longed for the day when he could fly such “big new jobs” as the Avro Lancaster and the Handley Page Halifax. Apparently he was giving up all thoughts of piloting the once favoured Beaufighter and Mosquito.

By early December he had been promoted Flying Officer and judged fit and ready to proceed to a front line operational unit. Appropriately this turned out to be No. 429 (Bison) Squadron, an RCAF outfit formed just weeks before at East Moor in Yorkshire and assigned temporarily to 4 Group. It was initially equipped, as Barney soon discovered, with the familiar Wellington bomber. Yet interestingly, his first operation was carried out not in a Wimpey but rather in one of the four-engined “jobs” he had recently been excited about. On 12 December, as a kind of initiation perhaps, he served as second pilot aboard a Halifax bound for Turin in northern Italy. He had, however, little time to savour the experience. The Halifax's hydraulics system failed en route and the raid had to be aborted. The Turin operation was the exception that proved the rule that for the rest of his stay at East Moor he saw service exclusively on the Wellington.

Before long Barney was in the thick of the action, piloting his Wellington III BK 162 (B for Baker), which, following common practice, was decorated with what he called “our lovely girl”, a look-alike drawing of popular movie star Betty Grable. His tightly knit crew would come to include an Englishman, wireless operator/air gunner Jim Smith, and three fellow Canadians, navigator Jack Kerr, bomb aimer Ian McIntosh, and tail gunner Jim Jakeman. As Barney told his Canadian correspondents most of them had met, bonded, and “crewed together, green as grass” at 22 OTU in the early fall of 1942, which to all of them, caught up in so many hectic events since, seemed “ages ago”.

Some of the crew's “ops” were so-called sea searches or operational sweeps over the North Sea, whose aim was to seek out and attack German surface craft. Others were quaintly dubbed “gardening”, a term used to describe mine-laying in enemy coastal waters. More often than not, however, land targets were the objective. But on a prospective raid against the French port of Lorient, a major U-boar base, Barney's Wellington was a victim of so-called friendly fire when it was “shot up” by a convoy and as a result was obliged to “return early” to base. The incident smacks of the one that had supposedly led to the death the year before of another former McMaster student, Stephen Goatley [HR].

There were other misadventures for Barney. Thus, after a raid on the Ruhr target of Duisburg in late March, he was plagued by mechanical problems and was forced to land at his base on one engine. Some two weeks later, again on a flight to embattled Duisburg, he was struck by enemy fire, the dreaded “flak” put up by high velocity .88s, the all-purpose artillery for which the Germans were renowned. Fortunately the damage inflicted was not deemed serious and he managed to return safely. Nineteen other aircraft, however, including 7 sister Wellingtons, were not so fortunate.

Other hazardous missions Barney would also complete, to industrial cities in the heavily bombed Ruhr such as Dortmund and Dusseldorf, as well as to Berlin, Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Aachen, and the much targeted U-boat pens at Brest in France. In the last-named engagement Barney had another ugly encounter with flak, this time a potentially more serious one. His Wellington's hydraulics system was disabled and the bomb bay doors were bent – though not before they served their purpose -- by the exploding .88 shell. Again he put his flying skills to work and successfully negotiated a safe return. Later he would speak of the experience of invading enemy skies, of “seeing another plane caught in a cone of … searchlights, and then, a few moments later, being themselves caught in another such cone, a situation which makes your plane an excellent target for [flak or] an enemy night fighter”. He also talked, reminiscent of other airmen's stories, of the “wonderful spirit of mutual dependence among the plane crews”.

Meanwhile the hazards continued to mount and to test that “mutual dependence” to the limit. On a raid against Mannheim on 16 April, carried out by 271 aircraft, including Barney's and 158 other Wellingtons, his was struck and damaged though not mortally. With the help of his crew he carried on and safely returned his aircraft to base. On this occasion the raiding force, while suffering moderate losses, was judged “effective”. It reportedly knocked out or severely damaged over forty “industrial premises” and rendered homeless nearly 7000 civilians, among them many factory workers. It was no accident perhaps that on the day following the Mannheim raid Barney was promoted Flight Lieutenant.

Thus by the spring of 1943 he had emerged as a seasoned and blooded veteran of the Bomber War. He had also gained the reputation of being, in the words of an impressed crewmate, a “pretty cool customer”, who more or less treated every raid as if it were a “cross-country” run. He had also proved a welcome morale booster. He helped to organize a squadron newspaper and, reminiscent of his submissions to WCI's Le Raconteur, contributed his observations, sometimes jocular, sometimes not, on 429's activities and accomplishments.

In August 1943, after he had continued to excel as pilot and commander under fire, he was posted for specialized training to Bomber Command's Tactics School where he spent the better part of a month before returning to his squadron. While at the school Barney was reminded of his days at WCI and McMaster and of his friend and former classmate, Bill McKeon, who had recently arrived in England with the Algonquin Regiment. Though he hoped to rendezvous with his friend there is no indication that he did so before Bill's death in Normandy in the summer of 1944.

In August 1943, after he had continued to excel as pilot and commander under fire, he was posted for specialized training to Bomber Command's Tactics School where he spent the better part of a month before returning to his squadron. While at the school Barney was reminded of his days at WCI and McMaster and of his friend and former classmate, Bill McKeon, who had recently arrived in England with the Algonquin Regiment. Though he hoped to rendezvous with his friend there is no indication that he did so before Bill's death in Normandy in the summer of 1944.

Barney had been back on operations only a matter of weeks when he received an even more gratifying species of recognition, the decoration known as the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). It marked, among other things, the completion (and survival) of a tour of operations, an impressive achievement. It also marked “in terms of danger and death”, a high-ranking Bomber Command officer brazenly ventured to claim, “… a far greater … contribution than that of any other fighting man, RAF, Navy or Army.” Understandably the citation accompanying Barney's award made no such invidious distinctions. Dated 4 October 1943, it read:

Flight Lieutenant Rawson has taken part in operations against the enemy on some of the most heavily defended targets in Germany. As acting flight commander and captain of aircraft, he has at all times set a fine example of courage, enthusiasm and devotion to duty.

Subsequently Barney, along with others so honoured, received his DFC form the hands of King George VI at a special Buckingham Palace ceremony attended by other members of the royal family. Barney wrote his sister, Norma, that “the King shook more than the ‘brave bomber pilot', and the Queen smiled sweetly”. He added what others had noted, that “Princess Elizabeth … is far more attractive than her pictures”.

On 3rd October, the night before Barney's citation was recorded, his Halifax along with 222 others in a 547-plane force had raided the industrial city of Kassel and inflicted heavy damage on two aircraft factories and several “military buildings” as well as, by chance, blowing up a large ammunition dump. He and his crew had again returned safely though twenty-four others had not, a moderate to heavy loss of life and aircraft. The Kassel operation – Barney's twenty-seventh -- was the only one in which he participated in the month of October.

During this brief, virtually combat-free respite most of his time was spent testing aircraft, conducting air-to-sea firing exercises, and, in anticipation of future mechanical problems, practising three-engined landings. He used some of his spare hours catching up on his correspondence with family. Thus on 15 October he hailed the arrival of their telegram congratulating him on his “gong”, that is, the recently conferred DFC. A week later he wrote half-jokingly that he had “got patriotic and purchased Victory Bonds”, a decision that would have pleased his father, who was often called upon to put his oratorical talents to work on behalf of bond drives in the Hamilton area.

Barney closed this particular letter on a more serious and disturbing note. He complained that his English uncle, Christopher Sexton, whom he visited on some of his leaves, had made disparaging remarks about the conduct of Canadian troops during the abortive and bloody Dieppe Raid of August, 1942. It mattered all the more that some of Barney's friends had been killed or wounded there while serving with the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry. “It was not exactly my idea of good taste”, he went on to remark, “for [him], a civilian, and an Englishman to take it on himself to criticize the Canadians”. Barney, like many other members of 6 Group, may already have run into this all too prevalent anti-“colonial” attitude.

The experience may have triggered the following jaded comment from this one time history student:

Lord knows, only the grace of God has saved them, the English, hundreds of times. Mark my words, if the English and Americans, or should I say North Americans, stick together on anything concrete after the war is over, then I'll be very, very surprised. At the present it looks extremely much like ‘every man for himself and the devil take the hindmost. I'll help you so long as I see my way clear to benefit by it'.

In another letter written some days later, Barney took issue with those who blithely thought that “the war would soon be over”. “Unless we forget that”, he cautioned, “and work harder than ever to finish this [war] it will be strung out for a longer time than it should be”. As a front line airman who on occasion had brought home shot-up aircraft and wounded crew members, he was only too well aware of a resilient enemy's' capacity to absorb heavy punishment and wreak havoc on its attackers.

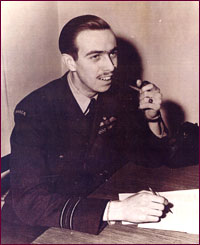

Interspersed with these somber reflections were the odd quips and jokes. For example, he disclosed to his parents that he had grown an “upper lip cover to keep out the cold” (more likely to mask his youthful features) and told them that he was looking forward to receiving a promised pipe. (Both the moustache and the pipe appear in the accompanying photograph.)

It was in the midst of his round of non-operational activities, three weeks to the day in fact after receiving his decoration, that Barney was promoted again, this time to Acting Squadron Leader. He was also placed second in command of 429, which by this time had left 4 Group and joined 6 (RCAF) Group, and was based at Leeming, Yorkshire. For the squadron there had been a change of weaponry as well as a change of scene. Barney's hope that he would soon be flying “four engined jobs” was finally redeemed when he took over the controls of one of the new “heavies” brought on stream, the Handley-Page Halifax, which had replaced the squadron's lighter Wellington the month before. Then after several operations he was on 27 November appointed to a staff position, Group Tactics Officer, another testament to his skill and experience.

While serving in that post Barney received a welcome visit from his father. Norman Rawson, the Great War veteran and popular preacher, gave widely acclaimed lectures on the war and other public issues, in the course of which he had come to the attention of officials in Ottawa. Realizing that he could do much good on the morale front at home, they sent him on a tour of Canadian bases in Britain. He was apparently given “carte blanche” to observe and interview and to publicize his impressions -- though certainly nothing that would compromise security -- on his return home. In due course he sought out, among others, bomber crews, including his son's. As Barney told the attentive Rev. Rawson, part of his assignment, in addition to actual operations against the enemy, was to visit the various group stations and lecture crews on the bombing offensive's latest tactical developments, now being actively promoted to reduce losses and maximize results.

To help maximize results personally in one of the most momentous enterprises of the war, Barney sought and obtained permission to take part in the events that swirled around D-day, 6 June 1944, the day that Allied forces made their dramatic landings in Normandy. On D-day + 1 he went on board a Lancaster as second pilot and participated in a raid on the Paris railway yards, aimed at disrupting enemy troop and supply movements behind the Normandy front. A week later he played the same role in a Halifax that along with others conducted a daylight attack “with fighter cover” on German defences and communications at the strategic Channel port of Boulogne, which lay in the path of the eventual Canadian advance along the coast. The Paris and Boulogne operations, his thirty-first and thirty-second, put him well into his second tour.

After his D-day plus sorties Barney returned to his staff position and resumed his tactics lecture tour, in the course of which he put in an appearance at Topcliffe, Yorkshire. It was the home of 425 Squadron, one of whose navigators was Flying Officer James (Jim) Cross, another former McMaster student who would also win the DFC. The next day, 23 July 1944, Jim excitedly wrote his parents about the visit:

Yesterday we were waiting for a tactics lecture when who should arrive to give it to us but Barney Rawson who was in my [history] course and year. He's a squadron leader now and has a DFC to boot, and he is only 21! We had quite a chat after the lecture. Barney now has a very important job with the Canadian Bomber Group. He's done at least one tour of ops and really knows his business.

All too soon the chat, enjoyed over a lunch, had to come to an end when the two airmen were obliged to return to their respective duties. They would not see one another again.

The “important job” that Jim Cross alluded to may have been Barney's impending appointment as Operations Officer at 62 (Beaver) Base, which served as 6 Group headquarters, and he would go there armed with a fresh promotion, to Acting Wing Commander. The Canadianized base, located at Allerton Park near Knaresborough, Yorkshire, had been formed in the summer of 1943 out of transferred RAF stations at Linton-on-Ouse and Tholthorpe. Like other occupants of Allerton Park, he might have come to know it as “Castle Dismal” , an epithet coined by a soured RCAF public relations officer.

Barney's primary responsibility as Operations Officer or Controller, as recalled by Robert (Bob) Westell, a fellow staff officer,

was to co-ordinate all details pertaining to daily operations. The Controller also held briefings on th[ose] … operations with the bases in Yorkshire This was done on a land line via “scrambler”. All bases were on what today we would call a conference call.

The “Ops Room”, which claimed the bulk of Barney's time and attention, was equipped with map tables showing, for example, the location of convoys, and was dominated by a large wall board. It recorded in chalk the names of air crew dispatched on missions and was invariably amended by grim erasures of those whose bearers failed to return.

On 17 November, Barney's staff duties came to an end, doubtless at his urging. Indeed at one point he had apparently grown “restless” with his non-operational role and sought unsuccessfully to arrange a transfer to the corps d'elite known as the Pathfinder Force (PFF), otherwise designated 8 Group. It was made up of crack pilots and navigators whose task was to improve the quality of precision bombing by locating and illuminating targets for the main attacking force. According to one account, Barney was under no illusions about the challenges posed by service in the PFF. In a conversation reported by an interested crewmate,

[Barney] told me you can expect anything on PFF. They train the sh.. out of you. You have to learn every other crew member's job, he said. A lot of it anyway, enough to be able to take over in an emergency.

In any case, these were the challenges that Barney wanted to meet head-on. His long-expressed wish was finally granted when he was appointed operational commander of the PFF Wing and attached to 8 Group's 405 Squadron, one of whose veteran navigators was Flying Officer Henry (Hank) Novak [HR], another former McMaster student. There is no indication that they ever met up with one another nor does the record show that Barney took part in the Zeitz raid that sadly claimed Hank's life on the night of 16/17 January 1945.

As Hank had done, Barney was now flying his own four-engined Lancaster and sporting the coveted Pathfinder Badge awarded him on 7 February. He piloted the Lancaster on a lengthy series of missions over the next two months, attacking an assortment of industrial and military targets and helping as well to pave the way for the advance of Allied ground forces, now at last fighting on the enemy's soil. These included the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, one of whose junior officers, Gordon Holder [HR], a McMaster graduate, was killed in the fighting on the Rhine front.

Barney flew his fifty-third and what turned out to be his final sortie on 9/10 April 1945, a month before the formal end of hostilities in Europe. His target this time was Kiel at the head of the strategic canal connecting the Baltic and North Seas. By any measurement it was a successful assault. German warships were capsized or otherwise badly damaged and the city's major shipyards laid waste. The enemy's anti-aircraft defences were all but overwhelmed: the massive 591 plane raiding force, almost exclusively Lancasters, suffered only three losses. Once again Barney himself came back unscathed. The Kiel raid, besides being his last, marked the completion of his second full tour of operations, an accomplishment that duly netted him a well deserved bar to his DFC. This time the citation read:

This officer has … participated in attacks against major targets in Germany and occupied territory. By his courage and determination to press home his attacks despite enemy opposition, he has contributed highly to the success of the squadron. Since the award of the Distinguished Flying Cross Wing Commander Rawson has continued to set a splendid example of skill and devotion to duty.

For all intents and purposes Barney's war was now over and he could begin to contemplate a departure for home. After the fighting in Europe formally ended on 6 May arrangements were set in train for his repatriation. A month later he was returned to Canada and on his arrival temporarily stationed at RCAF Trenton and given leave to visit overjoyed family and friends in Hamilton. Bob Westell, who returned on the same ship, remembers how Barney was looking forward to a “get-together” with him and other friends in thee very near future. For one reason or another, however, it never materialized.

By 20 September Barney, this newly returned veteran of the Bomber War, had received his formal discharge from the service and registered for law studies at Osgoode Hall in Toronto, the academic destination he had originally contemplated when he entered McMaster five years before. The Air Force official who oversaw his discharge was probably not surprised that Barney was accepted at Osgoode without the ordinarily prerequisite university degree to his credit. He had been struck perhaps not only by Barney's enviable high rank but by his “exceptional” brightness and keenness, the assets that had so impressed Air Force recruiters at the outset. Indeed, Osgoode Hall had readily admitted him as “a Matriculant without the required standing on grounds of military service”, his academic fees paid by the Department of Veterans Affairs. He wrote the fall term examinations and was articled to the Hamilton law firm of D.A.C. Martin. On the face of it, everything seemed to be falling neatly into place in the postwar circumstances in which he found himself.

Among other things, when he was not attending law lectures at Osgoode Hall, he accepted the speaking engagements that predictably came his way, including a well attended one at the local Kiwanis Club where he regaled his attentive audience with accounts of his war experiences. In this talk and others he characteristically made a point of praising not only his fellow air crew but the critical work of the ground personnel who had maintained, fuelled, armed, and otherwise prepared his squadron's aircraft for combat.

One day, leaving Toronto by train for home, Barney met up with several of his former McMaster classmates, among them, Allen Merritt, who recalled the good time they had on the short journey, exchanging tales of their alma mater and wartime days. They remarked on how high spirited and outgoing Barney was – in other words, he appeared to be his “old cheerful self”. Still another friend and former classmate, Norman Ryder, recalled that he and Barney, in the company of their “young ladies”, attended an affair at Burlington's popular Brant Inn. And presumably nothing seemed amiss. Some time later, however, Norman Shrive, another friend and Air Force veteran, met Barney over coffee at Renner's, a popular downtown rendezvous, and saw an entirely different Barney, a morose and cheerless one. In turn the medical student who shared quarters with Barney in Toronto recalled that his room mate had solemnly reflected on one occasion that death in a doomed aircraft would be the preferred one by far. Further, a Hamilton acquaintance recalled that occasionally Barney uncharacteristically and unsettlingly made a point of stressing his Air Force rank in casual conversations. Finally, the friend from Ottawa days, Gord McClatchie, who with his wife paid him a visit in Hamilton at about this time, said that Barney was complaining of insomnia or unnerving nightmares in the intervals in which he did catch some sleep. All these may have been among the crucial signals for the tragedy that lay ahead.

On 24 December 1945 -- the Hamilton Spectator reported the shocking news that on the day before, the “hero”, Barney Rawson, had “died suddenly” in the midst of the first peacetime Christmas festivities in years. What proved even more shocking, however, was the later revelation that he had in fact taken his own life after suffering what the Spectator called a “complete nervous breakdown”. It all happened barely three weeks after his twenty-third birthday. Turbulent wartime years full of high and heady responsibilities punctuated with the dangers that stalked the constant “pressing on” to one target after another had apparently caught up with him. In a case like Barney's severe post-traumatic stress disorder would in all likelihood be today's diagnosis.

His memorial service was conducted by his grieving father at Centenary Church in the presence of an overflow audience of civilian mourners and RCAF personnel of all ranks, including the so-called brass, who had come to pay their fond respects to a departed comrade. Among the Air Force veterans in attendance that day was Charles Harrison, a Hamiltonian who like Barney had attended Centenary's Sunday School as a boy and who had seen Barney on and off while both were serving with 6 Group overseas. He vividly recalled the emotion-laced Centenary service and its impact on the Rawson family.

For its part, McMaster University felt that Barney should be considered as eligible as the others whose names would appear on its planned World War II Honour Roll tablet, fashioned to commemorate those graduates and undergraduates who had not survived the conflict. A sympathetic George Gilmour, the Chancellor, asked for advice on this point from Jim Cross, who had resumed his studies at alma mater and was serving as chairman of the Veterans Committee. Jim, who had last seen his former classmate at a Yorkshire bomber base in the summer of 1944, heartily endorsed the idea Gilmour broached. As a result Barney's name was duly inscribed on the tablet subsequently installed in Alumni Memorial Hall.

C.M. Johnston

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: James Cross, Louise Derry, Charles Harrison, Grant Howell (see letter below), Michael Levett, Norma (Rawson) Levett, Susan Lewthwaite, William MacKinnon, Gordon McClatchie, Merle McClatchie, Allan Merritt, Linda Payne, Norman Ryder, Norman Shrive, Mark Steinacher, Eric Stofer (see below), Bernard Trotter, Sheila Turcon, Jack Watts, Robert Westell, and Kenneth Wilson (see below), all contributed vital help of varying kinds. Norma and Michael Levett offered very useful family history and recollections as well as such illuminating memorabilia as Barney Rawson's wartime letters (see NL below) and pilot's flying log book. Linda Payne, who also generously helped out with the Hank Novak biography, provided productive leads to internet sources. Wm. MacKinnon did the same for the Rev. Norman Rawson files at the United Church Archives (see below). Susan Lewthwaite of the Law Society of Upper Canada Archives supplied details of Barney Rawson's brief stint at Osgoode Hall. Charles Harrison and Robert Westell, both 6 Group veterans, furnished welcome memories of Barney Rawson. They as well as Gordon McClatchie and Eric Stofer were reached through Air Force Magazine , which readily printed requests for information in its section, “Vapour Trails”.

SOURCES: National Archives of Canada: Service Record of Wing Commander Byron N. F. Rawson, with accompanying documents detailing, for example, his early schooling and McMaster COTC service; NL: letters dated 24 Sept., 1 Oct. 1942, 19 Aug.,15, 22, 30 Oct, 2 Nov. 1943; letter from Norma Rawson to Grant Howell, 26 Aug. 1944; Brereton Greenhous, Stephen J. Harris et al, The Crucible of War, 1939-1945: The official History of the Royal Canadian Air Force, III (Toronto and Ottawa: University of Toronto Press and Department of National Defence , 1994), has many indexed entries for Squadron 429 (see, for example, the references on pp. 816-17, 820, 835); Spencer Dunmore, Wings for Victory: The Remark able Story of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan in Canada (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1994), 125, 349, 352; Spencer Dunmore and William Carter, Reap the Whirlwind: The Untold Story of 6 Group, Canada's Bomber Force of World War II (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1991), also has numerous indexed entries for Squadron 429 (see, for example, the information on pp. 110-13); Martin Middlebrook and Chris Everitt, The Bomber Command War Diaries: An Operational Reference Book (London: Penguin ed., 1990), 379, 436, 601, 632, 693, 768-9; D.C.T. Bennett, Pathfinder: A War Autobiography (Manchester: Crecy Publishing, 1998 ed.), chap. 6, and 217, 251, 253; Eric Stofer, Unsafe for Aircrew (Victoria: HERSS [self-published], 1995, 2nd printing),175, 314, 370-1, 375. (The author served as a flight engineer with 429 Squadron.)

United Church of Canada (UCC) / Victoria University Archives: Biographical File and Pension File, Rev. Norman Rawson, which happen to contain no reference to his son. (Information kindly supplied by UCC Archivist Kenneth Wilson); Westdale Collegiate Institute Library: Le Raconteur , 1940, 19, 21, 47, 62; Canadian Baptist Archives /McMaster Divinity College: McMaster University Student File, Byron N. F. Rawson, Biographical File, Byron N. F. Rawson; McMaster University Library, W. Ready Archives / Special Collections: Silhouette , 21 Nov. 1940, 22 Oct. 1943; McMaster Alumni News , 10 May, 15 Oct, and 10 Dec.1943, 15 Feb. 1944, 12 July 1945; Hamilton Public Library / Special Collections: Biographical File, Rev, Norman Rawson, Biographical File, Byron N. F. Rawson (consists of a newspaper obituary); Hamilton Spectator, 19 Oct. 1943, 1 Oct. and 24, 26 Dec. 1945; W. Stewart Wallace, “Webster, Lorne Campbell”, Macmillan D ictionary of Canadian Biography (Toronto: Macmillan, 1963, 3rd ed. rev.), 787.

Internet:

www.wellesbourne.fsnet.co.uk/history.htm;

www.raf.mod.uk/bombercommand/groups/h6gp.html;

www.rcaf.com/6group (“Daily Operations, Feb. 1943-- May 1944”);

www.429sqn.ca/ac09.htm;

www.raf.mod.uk/bombercommand/squadrons/h429.html;

www.rcaf.com/6group/rawsoncrew429.html; www.rcaf.com/6group/AllertonCastle/pages/6th.htm