Dr. C.M. Johnston's Project

Discover McMaster's World War II Honour Roll

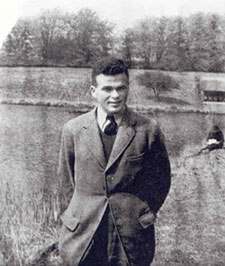

Thomas H. O'Neil

They Shall Grow Not Old, a helpful compilation published a half century after World War II, commemorates the some 17,000 RCAF personnel who died in that conflict. Its terse entry for Thomas (Tom) O'Neil reads:

They Shall Grow Not Old, a helpful compilation published a half century after World War II, commemorates the some 17,000 RCAF personnel who died in that conflict. Its terse entry for Thomas (Tom) O'Neil reads:

Killed in action Jan.3/43 age 20. # 39 Squadron … On January 3, 1943 [he and] the crew of Beaufort # DW 825 were making a very low approach to the practice target over a choppy sea in the Gulf of Suez. The aircraft appeared to touch the water, rise at an angle of 45 degrees with the port engine on fire and then crash into the sea

Hamiltonian Tom O'Neil was born on 22 August 1922. He joined a sister, Helen, and in due course was joined in turn by a brother, Kenneth, and another sister, Mary, all offspring of Thomas O'Neil, an accountant by profession, and the former Mary Gladys Moore, who had trained as a teacher. The father, a Great War veteran, became secretary-treasurer of a Hamilton automobile firm, Jolley Motors. Its president, Harold Jolley, was a cousin and close friend and his son, John, became equally friendly with Tom junior. As the O'Neils and others knew, the Jolley name was closely associated with Hamilton's early development. Harold's grandfather, James Jolley, Scottish native, Mountain resident, active citizen, and owner of a profitable saddlery and harness business in the city had funded the cut through the Escarpment that took his name and facilitated easier access to his downtown Hamilton enterprise. In the end the whole community benefited from the Jolley Cut.

Jolley Motors, the successor to the saddlery firm of the horse- and-buggy era, fell on lean times, however, when car sales slumped in the Depression-stricken ‘thirties. Thomas O'Neil's fortunes slumped with them. Then during the war when auto-making itself had to give way to a higher priority, the production of military vehicles, he was obliged to seek work elsewhere. He found it in the Income Tax Department in Hamilton, a federal position that came his way by virtue of his being a Great War veteran.

Meanwhile young Tom and his siblings were being raised in the Anglican faith of their parents and worshipping at St. Thomas Church, where a dutiful Tom taught Sunday School. He grew up on Mountain Avenue in the southwest section of Hamilton, attended the Bennetto and Earl Kitchener Schools, and then proceeded in 1935 to Hamilton Central Collegiate Institute (HCCI). There he clearly demonstrated his scholastic ability, capturing the

Carter Scholarship, emblematic of his achieving the highest aggregate standing on his senior matriculation examinations, with first class grades across the board. His favourite science subjects led the way. Other predictable laurels were to follow, including the Hamilton Spectator Prize in Science and English.

En route to these awards he had played a key role in two dissimilar activities at Central, journalism and rifle-shooting. His first major venture on Vox Lycei , the school's yearbook, was to take over the section known as "Exchanges”. It involved reviewing and excerpting humorous passages from the varied publications of other educational institutions, no light task. In a preamble Tom had this to say:

For many years most of the Exchange Editors have devoted some of their space in pointing out that the Exchange Department was not wholly useless. This year because I cannot think of any further arguments, I am letting the column speak for itself.

This no nonsense, not to mention mildly sardonic statement, probably characterized his general approach to problem-solving. In any case, he reportedly took on every task, journalistic or otherwise, with a "determination” that impressed one close high school friend, even if it was often accompanied by a marked shyness or "moodiness”.

In any event, Tom's diligent reviewing and editorial work for "Exchanges” proved a stepping stone to Vox Lycei's top post, Editor-in-Chief. As in his previous one, he obviously carried it off with considerable aplomb, fully earning the praise of his fellow students in "An Appreciation” extolling him for his "patience and hard work”. Still another student "extended his congratulations to Tom and his efficient staff for the splendid [1939-40] edition of the Vox”. "They have indeed upheld”, he added, "the high standards set by their predecessors”. It seems that Tom's prodigious work on the yearbook was a matter of concern for his parents who feared that it might intrude unduly on his studies. Their concern, as noted, proved groundless.

Meanwhile Tom came in for more commendation when he performed on the rifle range. Introduced to rifle shooting by his maternal grandfather, he honed his skill at HCCI under the inspired coaching of the already legendary Captain ("Cap”) J.R. Cornelius, who had also trained other Central marksmen, among them, Murray Bennetto [HR]. It would appear that the highly patriotic Cornelius was convinced that another war was well on the way and he was anxious to prepare his young charges for the worst, and this included enrolling the rifle team into the school's cadet corps, which he commanded. The policy did not sit well with local pacifists, who, haunted by the slaughter and carnage of the Great War, were still hoping for the best in spite of all the signs. Their influence, however, proved minimal and did nothing to sidetrack Cornelius' ambitious program or to deter Tom, this son of a Great War veteran.

Thus at meets in Hamilton and across the province he fully participated and in the process carried off top honours, usually in the commanding 95-100 range. In one contest he beat out a highly touted winner of a prestigious English award. On virtually every occasion, as the yearbook's "Military Matters” put it, the award-winning Tom ensured that HCCI was the "shining light of Hamilton Schools”. The column also reported that Tom was "always at his best” at the acclaimed Governor General's and Lieut. Governor's competitions in Ottawa and Toronto respectively. On the strength of these performances on the rifle range, which complemented his achievements in the classroom, he was named to Central's prestigious Lettermen's Association. In the circumstances it should come as no surprise that his younger sister, Mary, remembered him as the "golden boy” who invariably succeeded in everything he undertook.

In June 1940 the medal- bedecked marksman matriculated with honours from HCCI and briefly entered a more mundane world when he took a war-related summer job "making munitions” at the International Harvester Company, a local industrial landmark for nearly a half century. To get to and from when the parents were vacationing he relied on his car-driving sister, Helen, who for the purpose could conveniently borrow a vehicle from Jolley Motors. The brief Harvester stint not only helped satisfy Tom's patriotic urges but provided to boot the wherewithal to attend McMaster University and follow in the footsteps of his summer chauffeuse, another scholarship winner.

On his admissions application, made out in September, 1940, Tom predictably indicated that he "had no trouble getting set for study” , was no "crammer” or copious note-taker, and had little or no difficulty linking reading ad what he gleaned from lectures. All the same his faculty advisor reported that Tom's "reading time was generally slow though not in the "chemical languages”, among them German presumably. The professor went ob to allow that this freshman from Central did do "constructive work” and appeared to be spending the "full quota of time on his studies”. Again this would have come as good though expected news to Tom's parents.

On the extracurricular front Tom it seems expected to play football and to undertake as a matter of course the military training recently made compulsory for all male undergraduates in the McMaster Contingent of the Canadian Officers' Training Corps (COTC). For Tom it was a more structured and intensive program than that of the cadet corps in which he had participated at HCCI. Compulsory service in the COTC had been dictated by an Anglo-French military catastrophe overseas. The German Army, more or less dormant on the Western Front since the start of the war in September, 1939, had suddenly burst out and overwhelmed the Allied resistance. Indeed, the British Expeditionary Force was barely able to make its dramatic escape from Dunkirk in June, 1940 and most Canadians were fully expecting an enemy invasion of what that generation called the Mother Country.

These and other developments would bear heavily on newly minted McMaster registrants like Tom. Indeed they were put under no illusions that the year ahead would be a sombre one and that traditional peacetime activities would be curtailed if not abandoned altogether. At the same time the Mac Formal, the major social event of the session, was virtually turned over to the COTC' and in time transformed into the Military Ball, which all cadets were expected to attend in full uniform. All of this may have prompted the stark editorial that appeared in the student weekly, the Silhouette. asserting that time had run out for "Agnes Macphailism” - after the vocal social reformer and peace activist of the ‘thirties - and that an appropriately more martial mood must now take over. Initiations were among those hallowed institutions soon affected by the change. Some of its more boisterous events were suspended "for the duration” though Tom and other ‘Frosh” - among them, Hank Novak [HR] -- would still be obliged to wear the traditional green tie and to humble themselves before demanding upper classmen.

In the foreboding atmosphere of wartime Tom and his classmates, as best they could, knuckled down to their academic work. In Tom's case, given his ambition to become an industrial chemist, it was in Honour Chemistry and Physics, a demanding course revitalized by Professor Harry Thode, who had joined the science faculty the year before. Perhaps the heaviness of the course combined with the constantly nagging intrusion of the war to erode some of Tom's high school promise. In any case he finished his first year with a mixture of seconds and thirds, not his usual kind of performance, to be sure, but still good enough to retain his honour status.

While his academic record is plain for all to see, his extracurricular activities, if any, are decidedly not. A search through the Silhouette and the Marmor reveal no evidence of athletic activity or even membership in the Science Club, which honour students joined almost as a matter of course. Nor, like classmate Hank Novak [HR], did Tom show up for his freshman class picture. Perhaps his legendary shyness, bordering sometimes on aloofness, was a contributing factor. It may also account for his being rudely nicknamed "Toenail” by some of his insensitive classmates, who lived to rue their thoughtlessness.

In the end, for Tom all this proved irrelevant and purely academic in every sense of the term. Early in 1941, halfway through his year, he made up his mind to enlist for active service and made his intentions known. The McMaster Registrar, Elven Bengough, soon sent a requested letter to the RCAF officially confirming Toms standing at the University. Then on 5 June, with his year complete, he formally enlisted in Hamilton and was subsequently dispatched to the RCAF's 4 Auxiliary Manning Depot (AMD) at St. Hubert, Quebec. There he was introduced to the workings of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), designed to turn Canada into the "Aerodrome of Democracy”, that is, the training ground for Canadian and other Commonwealth aircrew for combat overseas. At St. Hubert he was not introduced to flying, however, but rather "airmanship”, on the face of it an oddly named exercise, which amounted to a good deal of drilling, route marching and other ground-based activities that more closely resembled an infantry course. He was also on the receiving end of medical inspections, inoculations, vaccinations, and a round of lectures and training films. Tall and fit, he had no problems with the medical examinations though his dark brown, curly hair must have been severely cropped by the routinely administered military haircut.

In the end, for Tom all this proved irrelevant and purely academic in every sense of the term. Early in 1941, halfway through his year, he made up his mind to enlist for active service and made his intentions known. The McMaster Registrar, Elven Bengough, soon sent a requested letter to the RCAF officially confirming Toms standing at the University. Then on 5 June, with his year complete, he formally enlisted in Hamilton and was subsequently dispatched to the RCAF's 4 Auxiliary Manning Depot (AMD) at St. Hubert, Quebec. There he was introduced to the workings of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), designed to turn Canada into the "Aerodrome of Democracy”, that is, the training ground for Canadian and other Commonwealth aircrew for combat overseas. At St. Hubert he was not introduced to flying, however, but rather "airmanship”, on the face of it an oddly named exercise, which amounted to a good deal of drilling, route marching and other ground-based activities that more closely resembled an infantry course. He was also on the receiving end of medical inspections, inoculations, vaccinations, and a round of lectures and training films. Tall and fit, he had no problems with the medical examinations though his dark brown, curly hair must have been severely cropped by the routinely administered military haircut.

Once the regimen at 4 AMD was completed, Tom, the aspiring airman, was assigned on 28 July to 1 Equipment Depot in nearby Montreal where he did the ritualistic guard duty that befell all new recruits while they awaited a posting to their first training assignment. In Tom's case this happened on 21 August when he was dispatched to 3 Initial Training School (ITS), located at Victoriaville, also in the Province of Quebec. After a series of aptitude, skill, and psychological tests - the latter deemed dubious by many trainees - Tom was selected not for pilot but navigational instruction, which this one-time model airplane builder may have regarded as a second best arrangement. On the other hand, he would have been perfectly at home in the navigator's seat, given his mathematical skills and especially his proficiency in calculus, talents which, of course, had not gone unnoticed at 3 ITS. What was important to Tom, however, was that he had been judged fit and ready for aircrew instruction. The next step, taken on 27 September, led to 10 Air Observer School (AOS) at Chatham, New Brunswick, one of the training stations headed up by a qualified civilian, in this case R.H. Bibly, a well known and respected bush pilot. At Chatham Tom trained on the twin-engined Avro Anson, a familiar fixture at most navigation schools across the country.

After spending a little over three months at 10 AOS he satisfactorily completed the course. In the process the one-time science major provided coaching help to an airman friend and fellow Hamiltonian, Stanley (Stan) Gentle, who unlike his benefactor had spent some time out of school and hence was mathematically rusty. Apparently Barney Rawson [HR] also lent a helping hand, the upshot of which was a grateful Stan's marked success in the navigation course. He had already introduced Tom to his sister Betty, whom Tom "courted” during most of his training time in Canada. They had instantly "clicked”, as she later put it, remarking that his well known shyness never seemed to mar their relationship. They fortunately shared a number of mutual interests, including a love of music, especially the modern species. Betty fondly recalled, for example, their enjoyment of such lavish Hollywood productions as the "Chocolate Soldier”, a film starring one of that generation's romantic duos, Jeannette McDonald and the screen Mountie,, Nelson Eddy.

Following a Christmas leave to visit Betty and the family, Tom was posted, as all fledgling navigators were, to a Bombing and Gunnery School (BGS). His turned out to be 4 BGS, located far from New Brunswick near the small farming community of Fingal in southwestern Ontario where Frank Zurbrigg [HR] also trained. Tom reported for duty there on 3 January 1942 and was promptly put to work on a variety of aircraft, ranging from the Anson to the Fairey Battle, an unsuccessful front line aircraft turned trainer. At some stations, perhaps at Fingal as well, the Battles arrived still bearing the wounds and grime of combat, a sober warning to all those who trained in them. Presumably taking the warning stride, on 14 February, after completing the course at Fingal, Tom was awarded his coveted Observer (O) wing and promoted from Leading Aircraftsman to Temporary Sergeant. The following day he was posted back to New Brunswick for instruction in the intensive astro-navigational course recently instituted at 2 ANS, Pennfield Ridge, where both Robert Edgar [HR] and Stephen Goatley [HR] trained.

Tom spent some six weeks effectively augmenting his navigational skills at Pennfield Ridge, the result of which was his gratifying appointment on 16 March to Pilot Officer. Flushed with this accomplishment, he was given a welcome two-week pre-embarkation leave to return home to a waiting family and close friends in Hamilton. A celebratory party was laid on at his parents' home on Mountain Avenue, attended by virtually every member of his extended family, including a cousin, Patricia Moore, who clearly recalled the festivities. Also on hand was an attentive Betty Gentle, who was well aware that time was rapidly running out on Tom's stay in Canada. Though not formally engaged the family sensed correctly that they had what their generation called an "understanding”. It could only have been reinforced at another graduation party staged for Tom at the warmly hospitable Jolley home on Concession Street. His cousin and old friend, John Jolley, who had joined the Navy, and Betty's brother, Stan, were also honoured. Fittingly, most of the guests may well have used the Jolley Cut to get to the party.

On 30 March, when his all too short leave came to an end, Tom said his goodbyes and was posted to 31 Operational Training Unit (O T U) located at Debert, Nova Scotia. An RAF installation, 31 O T U had been established to prepare aircrew for the grueling task undertaken by Ferry Command, organized in the dark days of 1940 to dispatch military aircraft from Canada directly to the United Kingdom. To this point there had been fewer than a hundred Atlantic air crossings but with the activation of Ferry Command such became regular and constant. All the same, those in the vanguard could be forgiven if they thought of themselves as virtual air pioneers.

As Ocean Bridge, the aptly named Ferry Command history, notes, those in charge of the training at Debert were on the lookout for particular attributes in their prospective trainees - quickwitttedness, initiative, above average mental and physical stamina, and a high level of proficiency. Thus Tom's selection for the program was a further tribute to the aptitudes and skills he had demonstrated in the BCATP. With other designated aircrew - a pilot and two wireless operator/air gunners -- he, serving as navigator, was put through a rigorous round of night flying and long distance exercises designed to prepare candidates for the protracted flight over the North Atlantic. Unlike those civilian and service personnel who operated a shuttle service to and from the United Kingdom, Tom was to be a "one tripper”, that is. he would make no return flight to Canada but rather proceed to other duties in the United Kingdom or elsewhere.

Having been cleared for departure on 1 May, Tom and his crewmates reported to the large embarkation base at Gander, Newfoundland and were introduced to their charge, a twin-engined, all-purpose Lockheed Hudson bomber. It was a tension-filled as well as exciting moment. The crew had been left in little doubt of the hazards, natural and man-made, that they might encounter on the mission, hazards that would ultimately claim the lives of 500 aircrew and bring about the loss of 150 aircraft.

With all preparations completed, Tom and his comrades took off from Gander on the evening of 3 May, climbed to the prescribed altitude over the sea, and set course for the British Isles. En route any number of things could have happened to thwart the flight - storms and high winds, faulty visibility, engine failure, mechanical problems with the reserve fuel tanks needed for the long trip, and not least the loss of the aircraft's oxygen supply, so vital a commodity at high altitudes.

It is not known whether Tom's Hudson experienced any of these potential disasters. What is known is that the19-year old's navigational talents met the challenge. After dawn mercifully broke and swept away the enveloping darkness, the jubilant crew soon had a sighting of Ireland far below. Their journey was almost over. Not long afterwards they made landfall safely and in one piece, "disemplaning” - the service record term -- at Prestwick, Scotland, the Ferry Command terminal. If their trip was typical it would have taken them some eleven hours to complete it. It must have been a relieved though tired crew that briefly celebrated their safe arrival, news of which they may have been permitted to cable their families.

After a brief respite and much enjoyed rest, Tom and his mates soon found themselves, as most New World arrivals did, at 3 Personnel Reception Centre in Bournemouth on the Channel. They were put up temporarily at the city's Majestic Hotel where Tom met and befriended an earlier Canadian arrival, Grant Ogilvie, a pilot from Saskatchewan. The older Grant, who appears to have taken Tom under his wing, had not been as fortunate as his new found friend for his Ferry Command aircraft had been forced to crash-land at sea. But he was in Bournemouth to tell the tale because he and other survivors had been rescued by the timely arrival of a Royal Navy destroyer.

Between lectures, medical tests, and other obligatory exercises, there was time for recreation at the Majestic Hotel. It included snooker playing, a game in which both Tom and Grant enthusiastically indulged. Grant recalled, however, what some of Tom's McMaster classmates had noted, that he was "quiet”, and moreover not disposed "to party with some of us” though he certainly knew how to have a "good time” in a less rambunctious way. All this led his impressed friend to conclude that Tom must have come from a "very fine family”.

A good many Ferry Command aircrew were ordinarily assigned to RAF Coastal Command but a "determined” Tom had already made up his mind that he much preferred another branch of the service. He put his name down for what he thought would be a more challenging pursuit in torpedo bombers, even if it was judged one of the "most dangerous”. For the requisite instruction he was obliged to journey to RAF Turnbury, on the windswept Ayrshire shore in Scotland where he arrived in mid-June 1942.

The operational training base was located on a requisitioned golf course surrounded by low hills. Apparently one of the least pleasant aspects of the place was its "mean-minded” chief flying instructor. He derisively addressed Tom and his compatriots as "colonials” throughout their stay on the station, an experience suffered elsewhere by fellow McMaster airmen, Albert Mildon [HR], Charlie Szumlinski [HR], and Murray Bennetto [HR]. But the "meanness” of the instructor was as nothing compared to the perils Tom encountered in his training, described by one senior officer as "not an occupation for the faint-hearted”. If anything this proved an understatement. It was generally conceded that the station suffered the highest accident rates in the United Kingdom, the result of exceedingly low level mock torpedo attacks on designated targets. As a result, morale on the station often plummeted, so much so that on one occasion no less person than Lord Trenchard, legendary Chief of the RAF Air Staff, put in appearance to boost the spirits of hapless trainees. In these otherwise distressing circumstances Tom still managed with the help of his crew and friends like Grant Ogilvie to celebrate his 20 th birthday.

Thankfully Tom and his bonded all- Canadian crew - he was its only officer -- were spared during their harrowing training session at Turnbury. While Tom navigated, Sergeant Gillmor Morrison did the piloting and Sergeants Douglas Cameron and George Walker served as wireless operator/air gunners. Then on 23 September they were all sent to RAF Abbotsinch near Glasgow for advanced instruction. After completing it, they were in late October pronounced fit and ready for operational duty and along with 13 other crews, including Grant Ogilvie's, were duly posted to the Middle East, scene of the raging Western Desert campaign against retreating Axis forces.

But before they embarked on their new assignment they were given a welcome week- long leave in London. They took in Canada House, the residence of the Canadian Hugh Commissioner, for a touch of home and then visited the celebrated albeit wartime-dimmed wonders of the sprawling metropolis. Then it was on to Southampton, where Tom, Grant and the others boarded a so-called New Zealand meat boat (the Tamaroa ) that would take them to the British West African colony of the Gold Voast (now Ghana), on the first leg of the long journey to Egypt, their ultimate destination. At the last minute apparently Tom and his comrades, deemed members of a "junior service”, were abruptly shifted from their comparatively comfortable quarters to the hold of the vessel in order to make room for a party of British Army officers. To the Canadians' great satisfaction most of those officers came down with violent bouts of sea sickness en route to the ship's destination. Meanwhile, for the Canadian airmen on board the long passage through the dangerous waters of the eastern Atlantic could only have reinforced the bonding process begun at Turnbury.

When the Tamaroa eventually docked at the port of Accra in the Gold Coast still another adventure lay in store for Tom and his comrades. After seeing nothing but water for days on end they were now about to observe little else but sandy deserts. Had Tom read Beau Geste or seen Foreign Legion films as a youngster he would be forcibly reminded of them on the journey he was about to take across the top of the African continent. He and Grant were once again assigned temporarily to ferry duty as "one-trippers”, this time flying twin-engined Bristol Blenheim bombers on the next lap of their roundabout trip to Egypt. Refueling and refreshment stops were made along the way in Chad and at Khartoum in the Sudan before Tom's and the other crews arrived safely in late December at their final stop in storied Cairo.

On New Year's Day, 1943 Tom and his friends were assigned to 39 RAF Squadron based at Shandur. The unit, which dated from the Great War, had been active in the Middle Eastern theatre ever since the summer of 1940 when Italy had entered the war on Germany's side. It had bombed targets in Italian- controlled Abyssinia and participated in British offensives in the Western Desert against Axis forces operating out of Libya. In the process the squadron had become one of the most multinational in the RAF, as Canadian arrivals like Tom would soon discover. In August, 1941 the squadron had received a supply of new twin-engined low-winged monoplanes that he and Grant would ultimately fly, the Bristol Beaufort. It served effectively as both torpedo member and reconnaissance aircraft and could reach a top speed of some 265 mph and carry nearly a ton of bombs or an 18-inch torpedo.

Regrettably Tom's service with 39 Squadron and his time aboard a Beaufort were extremely short-lived, indeed it lasted barely forty-eight hours. In an account that supplements the information in the opening paragraph of this biography, Grant Ogilvie painfully recalled the tragic circumstances that unfolded on 3 January 1943:

[That] morning Tom's crew and ours were out practicing torpedo runs on a ship on Suez Bay. We had just made a run in when they followed. We turned around to make another run when we heard the ship radio saying that an aircraft had hit the water, Tom was sitting in the nose and when it hit I guess he was thrown out along with Gil Morrison, the pilot. The ship asked us to fly around to search for other survivors but I guess Cameron and Walker didn't get out.

The official report stated that Tom's body was later recovered and that he had died of multiple injuries. His remains and those of Sergeant Morrison were buried in Suez War Memorial Cemetery, and a grieving Grant Ogilvie, together with his crew, served as pallbearers. The bodies of Sergeants Cameron and Walker were never recovered and the two airmen are commemorated instead at the Alamein War Memorial, the scene of the British 8 th Army's dramatic "Desert Victory” just weeks before.

For his part, Tom's father may all along have expected the shattering news. According to Helen's memory, she seemed to sense that her Great War veteran father, even if he understandably did not express it in so many words, believed that his war's successor would not be kind to his son. In any case, a week after

For his part, Tom's father may all along have expected the shattering news. According to Helen's memory, she seemed to sense that her Great War veteran father, even if he understandably did not express it in so many words, believed that his war's successor would not be kind to his son. In any case, a week after

Tom's death a memorial service was held in the family's place of worship, St. Thomas Church in Hamilton. Though Chancellor Howard Whidden and Dean Burton Hurd were away in Ottawa and Dean Charles Burke was indisposed, a sizeable contingent of McMaster representatives was on hand for the ceremony. Among the academics and administrators well known to that generation of students were Professors Chester New, Alfred Johns, Henry Dawes, and Dean Harold Stewart.

Not least was the presence also of the Registrar, Elven Bengough, who throughout the war maintained a close bond with McMaster armed forces personnel. On the day of Tom's service he wrote a moving letter of condolence to the O'Neil family, in which he assured them that Tom would always be proudly counted "as one of the college family” and that his name, with "sorrow and pride”, would be duly inscribed on the University's Honour Roll. It appears that Tom's would be the seventh name entered on that growing list of McMaster students and graduates killed in the line of duty. In the meantime, heartfelt eulogies had poured in from Central Collegiate where Tom had distinguished himself as student, journalist, and marksman. Leading the moving response were Principal A.W. Morris and Captain Cornelius, who, like Bengough at McMaster, had made a point of keeping in touch with his school's service personnel, who in turn showered him with letters and postcards.

Tom's close overseas friend, Grant Ogilvie, thankfully survived the war and, after serving in other theatres and other commands, returned home to farm in Saskatchewan and ultimately to share his valuable wartime memories with others.

C.M. Johnston

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Donald Brown, Patricia Burke, James Cross, Mary (O'Neil) Edwards, Kathleen Garay, Helen (O'Neil) Johnson, Joanna Johnson, Lorna Johnston, Peri Jolley, Kenneth Morgan, George Mowbray, Betty (Gentle) Nancekevill, Grant Ogilvie, Melissa Richer, Norman Ryder, Bernard Trotter, and Anne Wright, all made indispensable contributions to this biography. Grant Ogilvie (see below) provided a fine memoir that covered the long interval between RAF Turnbury, Scotland and Shandur, Egypt. He was reached through the courtesy of the "Vapour Trails” section of Air Force Magazine. Mary Edwards and Helen Johnson supplied vital O'Neil family history and other welcome information; and George Mowbray furnished acute memories of Tom O'Neil and like Donald Brown came up with productive leads.

SOURCES: National Archives of Canada: Service Record of Pilot Officer Thomas Harold O'Neil (includes two letters, one from Flight Lieutenant Milton A. Foss [rubberstamped signature], RCAF Casualties Officer, to Mrs. T. H. O'Neil, 20 Jan. 1943, the other from E.J. Bengough to Thomas O'Neil, 10 Jan. 1943; Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Commemorative Information on P/O Thomas Harold O'Neil; letter from Grant Ogilvie, undated (2004); Les Allison and Harry Hayward, They Shall Grow Not Old: A Book of Remembrance (Brandon MB: Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum Inc., 1996, 2 nd printing), 98, 539, 571, 789; Spencer Dunmore, Wings for Victory: The Remarkable Story of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan in Canada (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1995), 171, 354, 355, 360; Carl A. Christie, Ocean Bridge: The History of RAF Ferry Command (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995) especially chaps. 8 ("One-Trippers”) and 11 ("No Piece of Cake”).

Hamilton Public Library / Special Collections: Vox Lycei (HCCI yearbook), 1938-9, 11, 31, 1939-40 , [24], 25, 32; McMaster Divinity College / Canadian Baptist Archives: McMaster University Student File 7538, Thomas H. O'Neil, Biographical File, Thomas H. O'Neil (contains letter from Elven Bengough to Thomas O'Neil, 10 Jan. 1943), File on Helen O'Neil, '43; McMaster University Library / W. Ready Archives, Special Collections: Silhouette , 28 Nov. 1940, 4; Hamilton Spectator, 10 Jan. 1943; C.M. Johnston, The Head of the Lake: A History of Wentworth County (Hamilton: Wentworth County Council, 1967, 2 nd ed.), 86.

Internet:

"History of 39 Squadron” http://www.rafmarham.co.uk/organisation/39squadron/39shistory.htm;

"Review of Carl A. Christie's Ocean Bridge (see above), www.airpower.maxwell.af.mil/airchronicles/bookrev/chris.html