Dr. C.M. Johnston's Project

Discover McMaster's World War II Honour Roll

William A. McKeon

On 2 May 1922, William Allen (Bill) McKeon was born, a first child for Silas Albert and Martha (Young) McKeon of Hamilton, Ontario. The family lived in the east end of the city before moving to Herkimer Street and then to Bay Street South, a fashionable neighbourhood in the city's west end. In due course the family would come to include Bill's younger siblings, Charles and Margaret. They worshipped at what was then called the Basilica (now the Cathedral of Christ the King), the impressive Catholic edifice recently built in the Gothic style on the edge of Westdale, an affluent part of the city developed in the 1920s. Bill, like his brother and sister, was raised in the Catholic faith of his father. His mother, a native of Pennsylvania and a teacher by profession, had started religious life as a Presbyterian but later became a Christian Scientist. The father, identified only as a "salesman" on Bill's McMaster admissions application, must have been an enterprising one given the family's comparative prosperity. He was in fact a car salesman at the flourishing Dubois Automotive Company in Hamilton. Later, in common with so many others in the business world, he (and new auto sales) fell prey to the Depression that stalked the country in the 1930s. Hard times arrived for the McKeon family.

On 2 May 1922, William Allen (Bill) McKeon was born, a first child for Silas Albert and Martha (Young) McKeon of Hamilton, Ontario. The family lived in the east end of the city before moving to Herkimer Street and then to Bay Street South, a fashionable neighbourhood in the city's west end. In due course the family would come to include Bill's younger siblings, Charles and Margaret. They worshipped at what was then called the Basilica (now the Cathedral of Christ the King), the impressive Catholic edifice recently built in the Gothic style on the edge of Westdale, an affluent part of the city developed in the 1920s. Bill, like his brother and sister, was raised in the Catholic faith of his father. His mother, a native of Pennsylvania and a teacher by profession, had started religious life as a Presbyterian but later became a Christian Scientist. The father, identified only as a "salesman" on Bill's McMaster admissions application, must have been an enterprising one given the family's comparative prosperity. He was in fact a car salesman at the flourishing Dubois Automotive Company in Hamilton. Later, in common with so many others in the business world, he (and new auto sales) fell prey to the Depression that stalked the country in the 1930s. Hard times arrived for the McKeon family.

Meanwhile, in spite of financial difficulties, the children's schooling had to be arranged. Bill's formal education had begun at a local parochial school, St. Joseph's. After completing the necessary requirements there he progressed in 1936 to Cathedral High School, in the company of other Catholic youth who would later join him at McMaster and serve in World War II, among them Henry (Hank) Novak [HR]. But then Bill's mother intervened. Apparently she took exception to certain features of a Catholic education and arranged his transfer to a public institution, Westdale Collegiate Institute (WCI), a move in which her husband obviously acquiesced.

Eager to participate in extracurricular activities wherever he was, the high-spirited Bill soon made his presence felt at WCI. He became an active and valuable member of the school's Dramatic Club, performing in such productions as "Vickie", in which he starred as a convincing Archbishop of Canterbury. Off stage, he served on the Triune Executive, the governing student council. His activities did not end there. On the athletic front he performed well as a badminton and tennis player, in a manner reminiscent of Robert Dorsey [HR] at Hamilton Central Collegiate Institute. Indeed he may have been on one of the Westdale badminton teams that tried to take on the powerful Dorsey-coached McMaster squad in the late 'thirties.

Like Central's Murray Bennetto [HR] Bill joined his own school's rifle team. He wrote up its accomplishments for Le Raconteur, the student yearbook, to the dismay perhaps of those who thought such martial activities inappropriate in a society seeking to put the violence of the Great War behind it. Undeterred, Bill proudly reported that his team "was well supported by the students and the fine scores showed the results of diligent practice". In one competition he himself was the winner of a 2nd class medal, a testament to his reputed sharp eyes (doubtless enhanced by the corrective spectacles he wore). He eagerly supplemented his work on the rifle range - again reminiscent of Bennetto - with training in the school's cadet corps. He became so adept that he ended up as its commanding officer. While all this was going on he found time to earn pocket money by working part-time as a sales clerk in a local store.

In the classroom the versatile Bill also excelled, particularly in the science and French and German courses he took. Indeed, so well did he do academically that upon his matriculation from WCI in 1941 he was rewarded with a prestigious Rotary Club Scholarship. It was valued at some $600.00, an astronomical prize for that Depression-ravaged generation. (If the inflation factor were taken into account, this would amount in 2002 terms to some $7000.) Given the family's circumstances this must have been highly welcome news. The scholarship was more than enough to cover Bill's tuition and other fees, textbooks, and living expenses while attending McMaster University, where he had already planned to enroll for his post-secondary education. On his admissions application he listed as his principal referee Rev. Norman Rawson, the charismatic minister at the downtown Centenary United Church. Rawson also happened to be the father of Bill's Westdale friend and classmate, Byron (Barney) [HR], who may have introduced him to the clergyman's dynamic performances in the pulpit.

On an aptitude test that McMaster then conducted for incoming students, Bill revealed that he was not given to taking copious classroom notes. Nor apparently did he have difficulty linking what he gained from reading with information dispensed in class. Armed with these supposed attributes, and having indicated that he wished to become a chemical engineer, he registered in the formidable Honour Chemistry and Physics course (Course 40). Scientific German, a mandatory course for all science students, doubtless reinforced Bill's proficiency in the language he had studied so assiduously in high school. Course 40 itself had recently been galvanized by the appointment of Professor Harry Thode, who in his laboratories in Hamilton Hall would make significant contributions to war-related research. Before long Bill was actually caught up in some of the projects that unfolded under Thode's wartime supervision.

The war would soon be on everyone's mind. "In common with all male students", as his student file intones, Bill was obliged to enrol in the McMaster Contingent of the Canadian Officers' Training Corps (COTC). Not surprisingly, this former CO of the Westdale cadets readily accepted the obligation. As had Gordon Holder [HR], he did so as a full-fledged cadet, that is, with every intention of qualifying for a commission. Full of energy and enthusiasm, he crammed a good deal into the brief time spent at McMaster. Apart from his military responsibilities, this former Triune councillor also served on the university's Student Council after being elected president of his freshman year. As well, he ventured into such diverse activities as debating, boxing, wrestling, and working for the Board of Publications. On the badminton and tennis courts he continued to hone his skills, and not just on campus. A classmate recalled that Bill was an "excellent club player" at the tennis club organized at Trinity Baptist Church in the city. His cousin described him as "a demon on the courts", who along with brother Charles was virtually "unbeatable" at the Hamilton Tennis Club. But this flurry of extracurricular activity may account for his having to write some supplemental examinations to bring his standing up to the required honour level. This he succeeded in doing, thus retaining the Rotary Scholarship.

All this, however, turned out to be purely academic. Although Bill had announced plans to return to McMaster for the next session, he stayed for less than a term. Deciding it was time to enlist for active service, he journeyed to Toronto and signed on with the Canadian army on 6 November 1942. Before he left the campus, however, he performed one final service for his peers by editing the student Directory, and did so with his customary flair and efficiency. Within a week of his enlistment Cadet McKeon was dispatched first to a machine gun training centre at Trois-Rivieres, Quebec and then almost immediately to the Officers' Training Course (OTC) at the same place, an event that was noted by the Silhouette, the McMaster student weekly. "Good luck to you, Bill!" was the friendly editor's fervent wish.

Following the successful completion of the officers' course on 13 February 1943 Bill qualified for the rank of 2nd lieutenant and then followed the path more or less taken by all newly-minted officers. About a week after his promotion he was posted to Camp Borden where he undertook more training and served as an instructor. While so engaged he became qualified on 19 March 1943 for promotion to lieutenant. Late that month he found himself doing more instructing at No. 24 Basic Training Centre in Brampton. In late May his duties ended there and he returned to Borden. He shortly enjoyed a series of embarkation leaves to visit family and friends, a bittersweet interlude because it heralded his departure for overseas.

On one leave he visited his mother's relatives in Pennsylvania. Some people in the area mistook him for a youthful general because he sported what appeared to be two stars on his epaulets, the insignia of an American officer of that rank. The so-called swagger stick he carried, a stock accessory of the Canadian or British officer, doubtless enhanced the image. But his insignia were in fact the so-called pips that designated the more humble rank of lieutenant in the Canadian army. Whether or not that amused lieutenant disabused awestruck Americans of the notion that he was a general has gone unrecorded. In any case, when his older American cousin took him out to dine in local restaurants the friendly proprietors invariably extended the compliments of the house.

With his leaves and farewells behind him, Bill prepared for his departure from Canada. On 18 July 1943, he was formally assigned to the Canadian Army Overseas and shipped to Britain. After an uneventful Atlantic voyage he disembarked at his destination and shortly reported for duty. By mid-August he had been posted to the 4th Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit (CIRU) and its Officers' Refresher and Wireless Courses. At the end of the month he successfully emerged from them with a "Very Good" commendation. In September he entered and passed a course in tracked vehicle driving and the following month completed his assignment at the Officers' Refresher School. More assignments would follow. November found him posted to the 3rd CIRU and subsequently to the Algonquin Regiment. This unit, originating in North Bay, was made up for the most part of hard-working and hard-living loggers, miners, and farmers from all over northern Ontario. It had been mobilized in 1940 and, after a tour of duty in Newfoundland, was sent to the United Kingdom in the summer of 1943, only weeks before Bill arrived there. The unit would form part of the 10th Infantry Brigade, 4th Canadian Armoured Division.

Early in 1944, because of Bill's demonstrated quick-wittedness and grasp of foreign languages, he was picked for a prospective role in intelligence work. He seemed to fit the requirements in other respects as well, which called for "imagination and initiative", along with an ability to supervise others and to "express [one]self well". The upshot was that in March of that year, as a first step, he spent several days at the Royal Institute of International Affairs (RIIA) in London. Also known as Chatham House, this independent body had been formed in the interwar period to "encourage and facilitate the scientific study of international questions and to provide and maintain means of information upon international affairs". Now in wartime it was making its illuminating resources available to those in military service. While Bill was in attendance the RIIA's directors doubtless lectured him on the nature of the German foe and how best to deal with him.

The following month Bill was dispatched to the School of Military Intelligence, operated by the British Army's Intelligence Corps. In the desperate summer of 1940 it had been re-established to serve in another world war and was impressively housed in what had once been a mediaeval priory, located at a place quaintly called Chicksands. Although a Canadian Intelligence Corps had been set up in the fall of 1942, it was for a time, to quote a former officer who had dealings with it, nothing much more than "a squirrel's nest with a variety of odd pieces jammed together". Until it became the effective unit that it did, it often sent its own products to Chicksands for more specialized training. The British school set out to enhance the trainee's linguistic skills and acquaint him with interrogation procedures and the means of translating, analyzing, and interpreting enemy documents. Above all, it laid out the ways to protect one's own secrets and stressed the need to think the way the enemy did, better to anticipate his moves on the battlefield.

When the course ended a "passing out" ceremony was held for those who had made the grade, Bill among them. According to a plausible family account, Bill and others, in spite of Chicksands' aura and elegance, were so irritated by the patronizing rituals and imperious tone of the school that they gleefully marked the occasion by setting off a "stink bomb". Bill had always been given to practical jokes anyway so news of this episode apparently surprised no one. His unscheduled contribution to the proceedings had the desired effect. It seriously disrupted them and endangered the dignity of those in charge, some of whom may have haughtily treated the Canadians as mere "colonials", a not uncommon practice at English military installations. Bill, who would shortly be named the Algonquin Regiment's Intelligence Officer (IO), was never found out. Not for nothing would he soon acquire the sobriguet "Cowboy". War and the tedium of training had done little to dampen his high spirits.

The time to test what Bill had learned and been trained for came on 16 July 1944, some six weeks after the D-Day landings. As the regiment's IO, he was part of an advance party sent to Normandy to reconnoitre the area in which the rest of their comrades would be positioned and "inoculated" in battle. Initially, after the Algonquins arrived in strength on 26 July, they were teamed up with the 28th Armoured Regiment (British Columbia Regiment). In their first action as a group, however, they suffered heavily when they strayed from their planned axis of attack and fell prey to vigorously conducted German counter-measures. The 28th lost nearly fifty of its Sherman tanks and the Algonquins suffered the loss of two companies. It was a devastating baptism of fire. An Algonquin who was captured in the fight later recalled that it "was a horrible thing to see … [our] knocked out [tanks]. Once they were hit they would brew up, and you could see the guys trying to crawl out … and a lot of them were on fire". Bill mercifully survived these battles and the Algonquins' subsequent assault on Tilly la Campagne, which lay to the southwest of Caen, the key town taken by the Canadians earlier in the month.

The time to test what Bill had learned and been trained for came on 16 July 1944, some six weeks after the D-Day landings. As the regiment's IO, he was part of an advance party sent to Normandy to reconnoitre the area in which the rest of their comrades would be positioned and "inoculated" in battle. Initially, after the Algonquins arrived in strength on 26 July, they were teamed up with the 28th Armoured Regiment (British Columbia Regiment). In their first action as a group, however, they suffered heavily when they strayed from their planned axis of attack and fell prey to vigorously conducted German counter-measures. The 28th lost nearly fifty of its Sherman tanks and the Algonquins suffered the loss of two companies. It was a devastating baptism of fire. An Algonquin who was captured in the fight later recalled that it "was a horrible thing to see … [our] knocked out [tanks]. Once they were hit they would brew up, and you could see the guys trying to crawl out … and a lot of them were on fire". Bill mercifully survived these battles and the Algonquins' subsequent assault on Tilly la Campagne, which lay to the southwest of Caen, the key town taken by the Canadians earlier in the month.

Then it was on to another daunting task. The Algonquins, along with other Ontario units such as the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders and the Lincoln and Welland Regiment (the "Lincs"), were called upon to help close the so-called Falaise gap. The object of the exercise, labelled "Totalize", was, with the aid of the British on the flank and American forces moving up from the southwest, to entrap the German 7th Army, which was desperately seeking to escape and form a new front against the Allies. In the circumstances, the enemy set about to keep the gap open as long as possible and fought fiercely for every costly inch of ground on the road to Falaise, the very situation that Gordon Holder [HR] and the RHLI encountered in their turn. By now Falaise was but a battered shadow of its former self. It had been heavily bombed by both friend and foe and subjected to an almost unceasing Allied artillery bombardment designed to neutralize it as an enemy escape route. The Algonquins were in the thick of the action throughout the opening days of August 1944.

While all this was going on, Bill at one point reportedly embarked on an inspection and reconnaissance mission, in the course of which he came upon an American army depot. Well aware that the front-line Algonquins stood in dire need of some basic supplies, the affable and resourceful Bill succeeded in coaxing what he required from his accommodating hosts, probably all the while playing upon his American family credentials. The exercise had been time-consuming and he returned late to his unit, but he was obviously delighted, as were his fellow officers and the troops, with the welcome materials he had laboriously packed into his vehicle.

Meanwhile, by 14 August the Algonquins were mounting an attack in the company of Polish forces and other Canadian units, the Argylls and "Lincs" among them, to close the Falaise gap once and for all. This operation, which replaced the less than successful "Totalize", was eventually dubbed "Tractable", and featured an unprecedented and massive mechanized assault on the German positions protecting Falaise. Backed by artillery barrages and air strikes and screened by smoke, the operation began well. By the 15th the Laison River had been reached and crossed, with the Algonquins in the van. Thereafter, however, the going was slower as the desperate Germans reacted with their own armour and artillery. Even so, in spite of tactical reverses and heavy casualties in certain parts of the highly fluid and confused front the Canadians made progress.

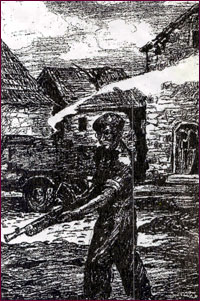

On 16 August the by now battle-hardened Algonquins were advancing on their next objective on the road to Falaise, the town of Marais-la-Chapelle in the Dives valley. Again as IO, Bill was in an advanced "recce party" or command group, this time probing the town's outskirts for a possible enemy presence. After he and the others satisfied themselves that the Germans had retreated from the area, the rest of the regiment was summoned forward. While awaiting its arrival, Bill's group, already standing in the centre of the town, suddenly spied two truck-loads of Germans entering and then abruptly stopping in the place. What followed has been well described in the Algonquins' exemplary regimental history, War Path:…

"the recce party opened fire with their pistols, and the Germans replied. At this point Lieut. McKeon (generally known as the "Cowboy"…) leaped to the C.O.'s scout car, wrenched the Bren gun from its rack, swung it on the German vehicles and let go several long bursts. The fire was extremely effective. One truck started up, then veered off into the ditch and burst into flames. The other never did get going. In a moment with five enemy dead, and four wounded, the rest surrendered, about fifteen in number. This quick action on the part of Lieut. McKeon certainly prevented what might have been a very costly encounter for the battalion command group."

Bill had clearly used his weapon as "a hose", to quote the stock phrase of the regiment's regular Bren gunners. After his dramatic exploit, more confused German prisoners were taken when they too blundered into Marais-la-Chapelle. Others were rounded up in the immediate vicinity by Bren gun crews and scouting infantry. Clearly the enemy's communications had been badly disrupted during the recent heavy fighting and he was unaware that his own forces had abandoned the town.

Following these developments, some of the Canadian units, including the Algonquins, were moved further east to provide a screen against a German breakout or a possible enemy attempt to relieve its endangered 7th Army. Although Falaise itself had finally been taken on 18 August a gap still remained through which the by now frantic Germans were seeking to escape. By 20 August Bill and the regiment found themselves on their immediate objective, a strategic promontory called Hill 240, some distance beyond the town of Ecorches. The next day, from that vantage point and others occupied by sister units, heavy fire was directed against columns of fleeing Germans. The unrelenting artillery and machine gun fire was ferociously augmented by attacks from the RAF's cannon-armed Typhoons ("Tiffies") and Spitfires. The slaughter and carnage - one Algonquin veteran in his reflective old age described it as "murder" -- went on for hours until finally the surviving Germans agreed to surrender. The traditional white flags appeared and in the company of German medical officers Algonquin orderlies were dispatched to tend to the wounded. It was reckoned that, apart from them, some one thousand German prisoners were corralled by the regiment that day. All the same, before the gap was effectively closed on 21 August 1944 by the meeting up of Canadian, Polish, and American forces at Chambois, thousands more Germans had managed to extricate themselves and live to fight another day. But they did so at the expense of leaving behind their precious armoured and mechanized equipment.

Among those interrogating German prisoners and inspecting their documents on 21 August was the Algonquins' IO, Lieutenant McKeon. While doing so, however, the unthinkable happened. Suddenly the whole area was raked with fire, directed not by the enemy as it turned out but by the Canadians' own artillery. Almost at once it inflicted casualties among both the Algonquins and their German prisoners. According to an eye-witness account, Bill "disdained to take cover" and ordered the regimental police guarding the prisoners to do so instead. But even as he spoke he was struck by a direct hit from the so-called friendly fire and died instantly. That fire only ceased after another officer frantically radioed the artillery battery to shut down. The damage, however, had been done and could not be undone. The survivors understandably cursed this turn of events but at the time it was difficult to distinguish friend from foe, particularly when they were so intermixed, as in this case. Nor was it the first or last time that this kind of tragedy occurred on the Normandy front. Earlier the advancing Canadians had in several instances suffered casualties when mistakenly bombed by Allied aircraft.

Not long after Bill's death, when more but not all of the details were made known to the family, his brother Charles told a concerned Arthur Burridge, McMaster University's Athletic Director, the essentials of what had happened in that "hot moment" of 21 August 1944. They had been conveyed by Major David Lynn, Bill's superior officer. Understandably Lynn had kept from Charles one piece of distressing information, namely that friendly fire had been responsible for his brother's death. That information only became public much later on.

At least "Cowboy" Bill McKeon, whose high spirits and zest for life had been his hallmarks, did live to see the final bloody stages of the closing of the Falaise gap and the decimation of the German 7th Army. An Allied "Break-out", after so many weeks of heavy combat, blood-letting, and frustration, was finally being achieved, and after 22 August 1944 the eastward pursuit of the foe became the order of the day. The Battle of Normandy was over. "There was no longer a danger", as one officer veteran reflected, "that we might be thrown back into the sea; nor a doubt that we would win the war". But the cost still to pay", he quickly added, "was uncertain". It would become a grim certainty soon enough.

In December 1944 Bill McKeon, a bold and seasoned participant in the Normandy campaign, was posthumously awarded a Certificate for Gallantry by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, Commander-in-Chief of the 21st Army Group in Northwest Europe. After the war Charles McKeon ('44) presented McMaster with the "Lieutenant W.A. McKeon Memorial Trophy", to be awarded for outstanding proficiency in badminton, Bill's favourite game. More recently his cousin, Elizabeth McKeon ('45) established a handsome McMaster scholarship in his name. David McKeon, a nephew, has served as the family's assiduous "keeper of the flame".

William Allen McKeon is buried in Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery, Calvados, France.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Gordon Guyatt, Sr., David McKeon, Elizabeth McKeon, Margaret McKeon, Mary McKeon, Sue (McDowell) McPetrie, Ernest Oksanen, Elizabeth Rode, Bernard Trotter, and Sheila Turcon provided essential help of various kinds, ranging from furnishing recollections, information, and documentation to archival and editorial assistance.

SOURCES: National Archives of Canada / Wartime Personnel Records: Service Record of Lieutenant William A. McKeon; Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Commemorative Information, Lieut. Wm. A. McKeon; G.L. Cassidy, War Path: From Tilly la Campagne to the Kusten Canal (Markham ON: Paperjacks, 1980 ed.), 108, 113, 118, 125; John Macfie, Sons of the Pioneers: Memories of Veterans of the Algonquin Regiment (Parry Sound ON: The Hay Press, 2001), 13, 25, 43, 48, 50, 111; Denis Whitaker and Shelagh Whitaker with Terry Copp, Victory at Falaise: The Soldiers' Story (Toronto: HarperCollins, 2000), 123-6, 163-7; Terry Copp and Robert Vogel, Maple Leaf Route: Falaise (Alma ON: Maple Leaf Route, 1983), 112-28; C.P. Stacey, Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War, III: The Victory Campaign: the Operations in North-West Europe, 1944-1945 (Ottawa, Queen's Printer, 1960), chap. X ("Normandy: Victory at Falaise").

Internet: www.lermuseum.org/ler/mh/wwii/inland.html, 3 pp.,

www.valourandhorror.com/DB/CHRON/Aug_13.htm, 2pp.;

www.army.mod.uk/intelligencecorps/history.htm, 2 pp., H. Skaarrup, Canadian Military Intelligence: A Short History, www.intbranch.org/inthist.htm;

Stephen King-Hall, Chatham House: A Brief Account of the Origins, Purposes, and Methods of the Royal Institute of International Affairs (London: Oxford University Press, 1937), 1; Pierre Berton, Marching as to War: Canada's Turbulent Years, 1899-1953 (Toronto: Anchor Canada, 2002) 363-4, 404; John Morgan Gray, Fun Tomorrow: Learning to be a Publisher and Much Else (Toronto: Macmillan, 1978), 268, 285.

Hamilton Public Library / Special Collections: W. McKeon, "Shooting", Raconteur, 1940, 65, also 49, [60], 63, 1941, 17, 41, [59], 64, 65; Canadian Baptist Archives / McMaster Divinity College: McMaster University Student File 7820, Wm. A. McKeon (admissions application), Biographical File, Wm. A. McKeon (letters from Charles McKeon to A.A. Burridge (n.d.), Martha McKeon to Burridge, 23 Nov. 1944); McMaster University Library / W. Ready Archives: Marmor, 1942, 59, 1943, 77-8, Silhouette, 24 Oct. 1941, 1, 6 Nov. 1942, 6.

[ For related biographies, see Nairn Stewart Boyd, Gordon Rosebrugh Holder, James Gordon Sloane ]