Dr. C.M. Johnston's Project

Discover McMaster's World War II Honour Roll

George E. Matchett

A curious visitor to the Canadian Dieppe War Cemetery at Hautot-sur-Mer in northern France may have paused before a modest grave marker bearing this information:

A curious visitor to the Canadian Dieppe War Cemetery at Hautot-sur-Mer in northern France may have paused before a modest grave marker bearing this information:

In memory of George Elwood Matchett

Captain Royal Hamilton Light infantry, R.C.I.C.

Died Wednesday, 19 August 1942. Age 32

The sobered visitor may have wondered who or what the man was behind the cryptic inscription and, as well, how he had ended up so violently in nearby Dieppe, a French town on the English Channel few Anglo-Canadians had heard of before the summer of 1942.

Though potentially revealing wartime correspondence has gone missing, answers to the questions, in whole or in part, are documented for the researcher. Elwood’s mother, Jane Grace (Gist) Matchett, whose heritage was English, gave birth to him in Hamilton on 6 July 1910. What turned out to be her last child joined two sisters, Ada Iola and Vera, and a brother, Roger. Before the Matchetts moved to Hamilton, where they welcomed Elwood into the family, they had lived in Peterborough, where the father, Montgomery Wellington Matchett, who claimed Irish extraction, was a well regarded elementary school principal. According to the 1911 Census, the relocated family resided initially at 22 Blyth Street before moving permanently to 90 Ontario Avenue. The six Matchetts came to worship at what was later called First United Church, an impressive mid-city edifice that stood out as the flagship of the United Church fleet in Hamilton.

Elwood’s education began in September, 1905 at Stinson Street School. He more than satisfied his teachers and was accelerated, graduating a matter of days before his thirteenth birthday. His next stop on the learning journey was Hamilton Collegiate Institute [hereafter Central], the city’s oldest secondary school. In this respect he blazed a trail trod by others whose names, like his, would ultimately appear on the Second World War Honour Roll of McMaster University commemorating those former students who did not survive the conflict.

Elwood made a good start at Central but later his Middle School grades were uneven, spiking in some instances and plummeting in others. As a result, his Middle School work was judged incomplete, his first but not last classroom setback. An analysis of various records indicate that his growing zest for the extracurricular impacted on his academic fortunes. He did well on the basketball court and in the wrestling ring but these diversions alone were not responsible. Plainly he was being wooed away from the academic by his first extracurricular love, target rifle shooting, to which he had been introduced in his tender primary school days.

At Central Elwood came to excel in the sport under the watchful eye of the school’s almost legendary coach, Captain (“Cap”) J.R. Cornelius, who had established his own reputation as a marksman in his native Scotland. His emergent rifle team, made up of Elwood and other aspiring sharpshooters, was an integral part of the Cadet Corps he organized and directed at the school. But in some quarters the program did not sit well, given the gory excesses of the recent Great War and the militarism it had fuelled. For their part, however, Elwood and his shooting mates seemed to have no qualms about joining Cornelius’ unit.

1927 proved a banner year for Central’s Rifle Team. A proud Vox Lycei, the school’s yearbook, left no reader uncertain on that point. Its prominent “Military Matters” feature exulted that “High records and wonderful achievements [of previous years] fell before the higher records and more wonderful achievements in 1927….” These words, obviously written by a participant with literary talents, went on to flesh out this general accolade. Central’s “well balanced” squad more than made up for an initial setback at a provincial meet in Long Branch” by an excellent showing in a Dominion-wide meet in Ottawa.

Elwood personally scored a string of bull’s-eyes in various categories, and in the process won, among other awards, the Whitney Cadet Aggregate (for the second time), and the Gooding Gold Medal. He also vitally contributed as a team player by helping his squad to win the United Empire Trophy and above all, the prestigious Victoria Rifles of Canada Cup, the latter deemed “possibly the most outstanding victory of the week”.

Yet these triumphs, noteworthy though they were, may have owed much, if not everything, to the extraordinary development that overtook Elwood and his fellow cadets two months before, during the long summer vacation. Captain Cornelius had long been seeking the restoration of the prewar practice of having Canadian cadets engage in friendly competition with English counterparts. In 1927 his ambition was finally realized when through his efforts and those of others in high places a prescribed number of superior marksmen on the Central Rifle Team received the signal honour of being allowed to accompany the Canadian Bisley Team to England. There they would participate in the jewel-in the- crown of all shooting matches in-the British Empire, those annually staged at the Bisley ranges near Brookwood in Surrey.

The Central detachment was made up of five crack shot finalists, in a stiff competition. A happy Elwood was one of those who made the cut. The deciding competition had featured for the first time in Canada the Bisley-mandated Lee Enfield .303, the British Army’s standard infantry weapon. En route to England the Central squad joined the Canadian Bisley Team in Montreal where the cadets were inspected and wished bon voyage by officials of the Dominion Rifle Association, an impressive and exciting send off.

In early June they embarked for overseas on the Cunard RMS Ausonia, a passenger ship that provided the Canadian adolescents with many an amenity, among them first class food, dancing to an orchestra, assorted deck games and lengthy bridge tournaments. On their arrival at Tilbury on the Thames, eight days after their departure from Canada, they were whisked off to the Bisley ranges. The first-ever trans-Atlantic experience must have been exhilarating and eye-popping for the unworldly teenagers. At Bisley they were comfortably lodged in the same accommodations as the Canadian Bisley Team.

The first two weeks of their stay were spent on the practice range where their performance earned the praise of English public schoolboys practicing alongside them. The gratifying session was followed by a well received two-day visit to London, the storied metropolis of the Empire. Though the brief stay sharply limited their itinerary, they still managed to savour some of the sights and sounds of the capital, using Trafalgar Square, their temporary abode, as their operating base. Then it was back to the main event, the formal shooting matches at Bisley. Over the next two weeks the Canadian Team did exceedingly well and clearly demonstrated that it had deserved its hour at Bisley.

For its part, the Central squad made its own valuable contribution to the overall effort, one of its members scoring highly enough to be judged “one of the best marksmen of the Empire”. Meanwhile Elwood more than did his bit until the final rounds in his categories when a malfunctioning Lee Enfield knocked him out of contention. All the same he could treasure an ornate telescope he had won as a prize along the way. When the Bisley meet closed the Central cadets were treated to a trip through the varied English countryside to the historic Scottish city of Edinburgh. Here they were received royally during their four-day stay, a preview of the reception accorded Canadian servicemen in the Second World War.

Among other pleasantries, the presumably awestruck Elwood and his team mates were invited to dine with a member of the local nobility, who also directed them to the city’s many historic sites. After Edinburgh the Canadians started on their return journey, travelling across Scotland to Greenock where they boarded a ship for Canada, the White Star liner, Regina. The return crossing was uneventful save for the sighting of many icebergs, the scourge of the ill- fated Titanic just fifteen years before, a tragedy known to every schoolboy on board.

After arriving unscathed in Montreal, the young Canadians were given the red carpet treatment at a local cartridge firm before entraining for Hamilton. Whether the five realized it or not, their Bisley achievement had helped enhance Canada’s reputation in the Empire, this fittingly on the sixtieth anniversary of Confederation. In due course the jubilant Central team was resoundingly welcomed in Hamilton and above all, at their gratified collegiate. As the local marksmen soon realized, their time overseas, as noted, had been a gold-plated learning experience that would boost their showing in future competition, both provincially and nation-wide.

Soon enough, however, the tumult and the cheering faded away. For Elwood it was time to return to earth and face the realities of life in the classroom. He would have been the first to concede that his record there fell considerably short of his remarkable performance on the rifle range. The year before he left for Bisley he was unable to complete the work of Middle School, a default that put him at a disadvantage when he ventured into the more demanding tasks of Upper School. Although he ultimately cleared the rest of his Middle School requirements, his Upper School record fell short of the mark and as a consequence he decamped from Central without formally matriculating.

According to information entered on his high school records, Elwood subsequently went to Detroit to take a dental technician’s course so that he could help manage the lab operated by his supportive dentist brother, Roger. But his time on the job was interrupted in the summer of 1932. Presumably with Roger’s blessing, he accepted another invitation to Bisley, this time as a 2nd lieutenant in a local militia unit he had joined after leaving Central, namely the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (RHLI), formerly the Wentworth Regiment, a venerable one by Canadian standards. He and a fellow militia officer were assigned to the Canadian Bisley Team and duly helped it win a coveted trophy on the by now familiar Surrey ranges.

Following his return to Canada, Elwood seems to have discarded the dental lab work and opted for another calling, which he may have been contemplating for some time. In spite of his academic shortfall at Central, he was apparently bent on a post-secondary education and a possible high school teaching career, perhaps somewhat ironic in the circumstances. On the other hand, he may have been inspired by the role model teaching and leadership qualities of Central’s “Cap” Cornelius. Even so, how could Elwood overcome the discrepancy between his hopes and his credentials?

McMaster University came up with the answer. This Baptist institution, recently relocated from Toronto to Hamilton’s Westdale district, offered a so-called General Course, roughly the equivalent of the Upper School education Elwood had not completed. If successfully cleared, the General Course invariably served as a passport to a conventional three or four year- degree program. The eager Elwood jumped at the chance and after being formally admitted by McMaster he registered in the sought after General Course in October, 1932. The process may have been expedited by his having listed as a referee a prominent businessman in nearby Winona , E.D. Smith, a jam and jelly maker, for whom Elwood may have worked the summer before appearing on McMaster’s doorstep. Another factor in his favour was that at age 22 he was a comparatively mature and well travelled student, who had met the challenges of the work-a-day world and was now clearly anxious to better his lot in life. His much publicized prowess on the rifle range and his award-winning trips to Bisley may also have helped his cause though it could have been a mixed blessing. Those Baptists of a strong pacifist persuasion would not have readily welcomed any such military-like exercise in peacetime.

At any rate, the admissible Elwood effectively handed the General Courses and in September, 1933 registered in Course 23, Honour English and History. So far, so good. Within a matter of weeks, however, dark clouds appeared on his otherwise sunny horizon. Late in the first term he was starkly told by the Dean of Arts, Professor W.S. McLay, what he already knew and regretted, that he was missing too many classes and consequently coming up short in the class work that counted toward his final grades.

In one of several petitions to the dean, Elwood pleaded lack of funds, which had obliged him to work off campus on Saturdays when several of his classes were scheduled. In another petition he requested more time off than the normal Christmas break allowed so that he might log more working hours at the T. Eaton Company’s down town department store, which traditionally hired students during the busy Yuletide season. Apparently this request was granted on what amounts to charitable grounds though a stern letter shortly followed telling Elwood that he must make up the missed work and achieve and maintain his honour standing. He made an effort to comply but the results were uneven. In some instances he did reasonably well, in others he ominously fell “below the line”.

| RIFLE TEAM

|

|

| Park, Humber, Howard, Bennetto, McLeish, Tucker, Ross McWhirter, Matchett, Warrender, Barelay |

In all likelihood the ongoing need to feed his famished wallet and to keep up his beloved rifle shooting, badly intruded on his academic timetable. Indeed in November, 1933, at about the time Elwood was seeking the dean’s forbearance, he was planting the seed of what later flowered as the McMaster Rifle Team. With the Dominion Intercollegiate Rifle Association matches just around the corner, he speedily cobbled together some dozen enthusiastic undergraduate sharpshooters, some of whom, however, had not recently been on a rifle range. After a limited but lively shooting practice they, with Elwood in the lead, were in time to join the inter-varsity competition staged in Toronto.

The Marmor, the student yearbook, highlighted this extracurricular initiative and accomplishment:

The year of 193[3] marked the inception of a rifle team. Through the efforts of E. Matchett, who was chosen captain, the team was hurriedly formed and entered in the Canadian Intercollegiate Rifle Meet. The team finished in third place, losing only to U. New Brunswick and Queen’s. This was a particularly fine achievement in view of the fact that the team had only one day’s practice. May success crown their efforts next year.

Success did indeed crown their efforts thanks in large part to Elwood’s work as manager and coach.

With the start of the 1934-35 session, however, he apparently did so as an outsider. It was a bittersweet situation. The previous spring he had been advised that he had failed his year in Course 23 and that he would have to repeat it. There is no evidence that he did so, and he must have been invited back on campus for the sole purpose of guiding the rifle team he had founded and seen accepted as a regular part of the extracurricular program. In any case, by 1936, his coaching arrangement with the team had ended and he was embarked on other ventures beyond the campus.

One such venture pushed Elwood’s passion for the rifle range into second place, namely his marriage to Elizabeth Dunnachie. To meet his new domestic responsibilities, he took on a salesman’s job with the Coca Cola Company, which may have required considerable travel in the Niagara Falls area. All the same, he hardly forsook the military matters that had hitherto consumed much of his energy. Though McMaster had had no COTC unit he could have joined, he had throughout maintained his close connection with the RHLI. For Elwood 1937 would be as much a banner year as 1927 or 1932, when he was invited to join the Bisley Team not as an associate, but as a full-fledged adult member, qualified to compete overseas.

The Britain Elwood revisited in 1937, was not the same comparatively tranquil country he had travelled through as a callow teenager ten years before. What that generation of Canadians called the Mother Country was still reeling from the domestic crisis triggered by the abdication of Edward VIII. At the same time, it was warily looking over its shoulder at the rise of aggressive Fascist dictatorships in Germany, Italy, and Spain. Against this sobering backdrop the latest edition of the Bisley matches unfolded. True to his winning ways with the rifle, Elwood carried off a raft of awards and prizes, among them, the Grand Aggregate, the All- Comers Aggregate, the Duke of Gloucester Prize and the Silver Cross in the stiff St. George’s Competition.

On this occasion as on others, he displayed his trademark modesty and honesty. When he spoke to an admiring reporter from the Montreal Gazette following his return to Canada in late July, he simply remarked: “Anyone on the team might have won them, it just happened to be me”. All the same, the Globe and Mail proclaimed:

Those who go to Bisley are far more than good shots; they are men with a recognized standing gained in national and international competition, which is enough to place Lieut. Matchett high up among the world’s best.

After his arrival in Hamilton to plaudits and a reunion with Elizabeth, Elwood resumed his day job at Coca- Cola and his militia responsibilities with the RHLI. But the applause did not fade away. At the Hamilton Armories in early October he was honoured with a ceremonial dinner, attended by, among many other dignitaries, his old Central mentor, “Cap” Cornelius. Surrounded by his Bisley trophies, Elwood was again characteristically self effacing and went out of his way to thank the regiment for its support of his efforts.

Henceforth his militia duties took on a far greater meaning. Heart-stopping events around the globe saw to that. Newspapers were soon full of the Japanese invasion of China, the ideologically charged Spanish Civil War, the Italian conquest of Abyssinia, and the Munich crisis and subsequent German dismemberment and then takeover of Czechoslovakia. In late August 1939, as the overseas crisis deepened, Berlin concluded the unthinkable, a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union, thereby removing a possible threat on Nazi Germany’s eastern flank. In the circumstances another general war seemed all but inevitable. Among other steps taken, Ottawa for its part mobilized several Non-Permanent Militia units. A few days later, on 1 September 1939, Nazi Germany pulled the dreaded war trigger by invading Poland. This in turn activated – if that is the right word an Anglo-French commitment to come to Poland’s aid, an undertaking made after the alarming events in Czechoslovakia. What would shortly become another all-encompassing world war involving Canada had begun.

Even before Britain and France formally declared war on their old enemy on September 3rd and Canada’s similar response a week later, the twenty-nine year-old Elwood threw his own hat in the ring. The day after German troops and armour rolled into Poland, he left Niagara Falls, where he and his wife were then residing, and journeyed to Hamilton to enlist for active service with his old regiment, the RHLI, which was in the throes of its own mobilization. In the midst of all this Elwood was duly attested and documented. As well, he was appointed captain, his old militia rank, on the strength of his lengthy and productive peacetime service.

Officers like Elwood had their work cut out for them, overseeing, among other tasks, whatever basic training could be arranged for the green rank and file that had recently rallied to the RHLI’s standard. It was early days and much would have to be improvised and organized, including the acquisition of proper uniforms and equipment. At the dawn of 1940, after regularly constituted companies were formed, Elwood was made second–in-command of B Company, the unit he would serve at home and eventually overseas.

Meanwhile, after Nazi Germany’s swift conquest of Poland there was little or no action on what the Great War generation had called the Western Front, even if a limited though ferocious conflict had flared up between the Soviet Union and Finland on the eastern corner of the Continent. “All Quiet on the Western Front”, the classic phrase of the Great War, now took on a new meaning and was rudely changed to Phoney War to describe the military inertia that lasted until the following spring. Phoney War or not, the RHLI soldiered on to become a force fit to serve overseas. Elwood was doubtless involved though his service record provides no details until an entry was made on 6 June 1940 to the effect that he was being attached to a headquarters unit.

Just two days before, news had arrived that a desperate evacuation of a battered British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and a large body of French troops had finally been completed from the Continent. The question of the day was, how had this unimaginable turn of events come about, no inkling of which had appeared in Elwood’s service record? Barely a month before, on May 10th, the Western Front of old had been cracked wide open by the hammer blows of a combined German ground and air Blizkrieg. Within a month it was all but over. Holland and Belgium were quickly subdued and the whole of the BEF was threatened with encirclement and destruction if it could not escape by sea. In spite of doubters and skeptics that escape was arranged by the successful evacuation at Dunkirk by the Royal Navy and private boat owners. Though that seemingly providential deliverance created a wartime lore of its own, there was no hiding the fact that Britain had suffered a humiliating defeat and that after France subsequently fell, she faced as well the full might of Nazi Germany and a likely invasion, an operation dubbed “Sea Lion”.

These ominous game-changing developments speeded up and intensified the training of such units as the RHLI, this time at Camp Borden, long the country’s premier training base. In early July word was received that an overseas sailing was in the offing and soon embarkation leaves were being issued to Elwood and his fellow Rileys. After the leaves ended, they spent some days at the marshalling depot at Debert, Nova Scotia, before proceeding to Halifax, the busy overseas departure point for so many thousands of Canadian service personnel during the Second World War.

On 23 July 1940 Elwood and 880 officers and men of the RHLI boarded the Cunard White Star liner, Antonia, and set course for the UK in convoy with other troopships and an escort of Royal Navy vessels, two cruisers and four destroyers. For Elwood, the seasoned Atlantic traveler, it was his fourth known trip to the UK, this time, however, not to a pleasurable peacetime rifle shoot but to some kill-or-be-killed battlefield. The convoy made it safely through U-boat hunting grounds even if the Antonia had at one point a dangerously close encounter with a sister troopship. On 2nd August, after a 10-day crossing, Elwood sighted Scotland, the land he had briefly toured as an adolescent. The Antonia docked at Greenock on the Firth of Clyde and landed its uniformed passengers. Though there is no record of it, Elwood may have joined others in sending the customary cable home, telling of the ship’s safe arrival.

On the following day, the regiment left their sea legs behind and entrained for the south of England and the prospective invasion zone. As they rode through wartime Britain, excitement rollercoastered with apprehension as they contemplated what lay ahead. Their destination was the Corunna Barracks in the sprawling military camp at Aldershot, which had accommodated thousands of Canadians in the Great War. On arrival, they were formally incorporated into the recently formed 2nd Canadian Division. The RHLI soon discovered, however, that it woefully lacked essential equipment, notably motor transport, Bren Gun Carriers, and anti-tank weapons. Understandably the bulk of these essentials had been consigned to the counter-invasion troops deployed on the Channel coast, some of whom were Canadians who had preceded the Rileys to the UK.

While they were settling into their new home, fierce battles raged overhead between the Luftwaffe and RAF Fighter Command, the outcome of which could settle Britain’s fate one way or the other. In mid-August the regiment got a mild taste of what London was now suffering when a German aircraft dropped bombs close to its Aldershot quarters. Unlike London’s bitter experience, no casualties or damage resulted at Aldershot. Elwood may have missed the excitement because he was apparently on a so-called landing leave at the time.

Yet he was on hand when graver dangers loomed. In early September the regiment was readied to confront a reported enemy airborne assault, the like of which had helped to overwhelm the Dutch four months before. Then a few days later the RHLI and other units were ordered to prepare as best they could for a reportedly imminent German invasion attempt. But much to the relief of all concerned on the English side of the Channel, these potentially lethal intrusions did not occur. Still the Canadians had to keep up their guard to deal with the real thing and to that end underwent more intensive training, this time with the welcome “practical equipment”, including some motor transport, they had hitherto lacked.

While these precautionary steps were being taken, it became apparent after mid-September 1940 that the Luftwaffe’s daytime bombardment was sharply ebbing away, a cheered signal that Fighter Command had finally won the day in the so-called Battle of Britain, though admittedly by a narrow margin. By denying thee Germans mastery of the skies over Britain, the RAF, in conjunction with the Royal Navy in home waters, made an enemy cross-Channel thrust highly problematic.

Against this backdrop, how did Elwood Matchett fit into the picture? Unfortunately his service record resembles a wartime ration book, in the sense of allowing no meaty day-to-day or week-to- week entries on his activities. What is disclosed is that he was granted a short Christmas leave in 1940. Where, how, or with whom he spent it is left to the reader’s imagination. Perhaps he took the time to pay a nostalgic visit to Bisley, where he had enjoyed so many marksmanship triumphs before the war. The next entry appears on 22 February 1941 when Elwood was ordered to enroll in a Regimental and Officers’ Security Course. He apparently completed it and returned to Aldershot on March 3rd, the last dated entry before the events of the late summer of 1942.

Thankfully the RHLI’s War Diary and its fine regimental history, Semper Paratus, more than take up the slack. For example, they record that counter-offensive infantry tactics were constantly practised along with combined schemes involving armoured units. To help relieve the monotony of this relentless training, the RHLI’s Commanding Officer (CO), Lieut.-Colonel Robert Labatt, instructed his officers and men to use their free time to establish neighbourly relations with the locals in the general area of the camp. Elwood doubtless became part of this well-intentioned morale-boosting program.

Then in the opening days of the 1941 summer season, Elwood and anyone else with access to a radio or a newspaper, learned that the whole war scene had changed dramatically. After abandoning “Sea Lion”, Nazi Germany had turned its attention eastward. On 22 June 1941, following its conquest of Yugoslavia, Greece, and Crete, it torched its pact with the Soviet Union and invaded that country. Codenamed “Barbarossa”, it unleashed a tsunami of crises whose ripples eventually lapped at the barracks of the RHLI and other Canadian units stationed on the other side of Europe. Then in late 1941 the war became truly global when the United States entered the conflict by virtue of the bold Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which set off another military tsunami that would also profoundly affect the future of Canadian troops.

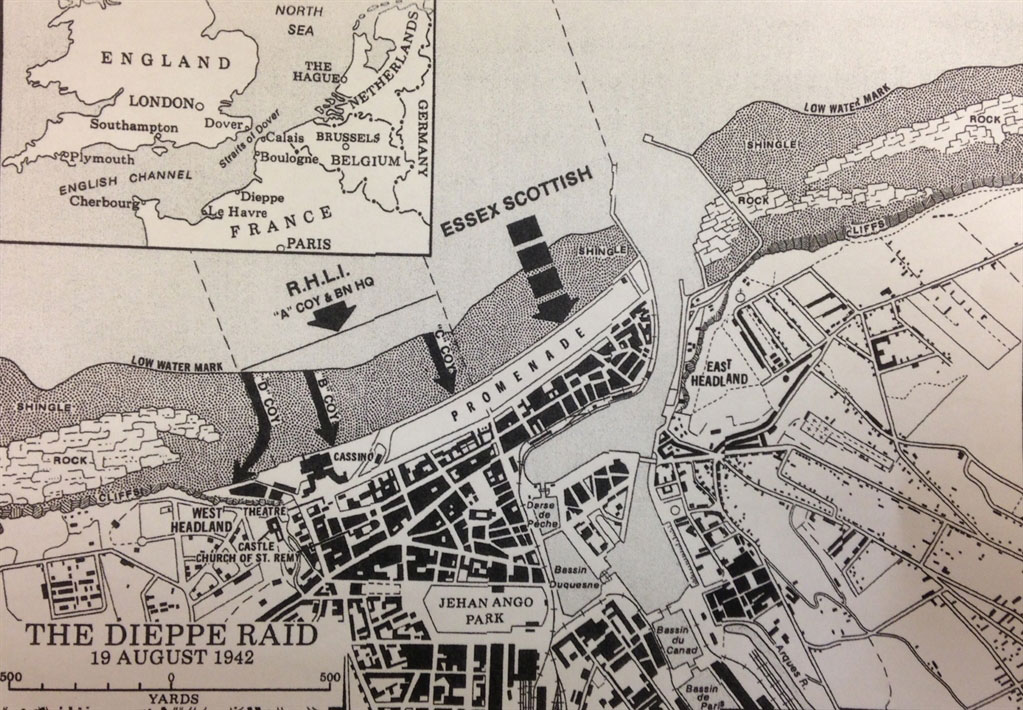

While these world-encompassing events were playing out in the early months of 1942, the Canadians in England were still mainly engaged in counter-invasion manoeuvres. But in April Elwood and his fellow officers sensed a change in direction, from the purely defensive to the counter offensive. This was soon confirmed when they were ordered to attend and observe demonstrations of assault landings at Portsmouth and elsewhere. The British were indeed in the midst of organizing an amphibious operation that would dwarf the modest hit and run commando raids of post-Dunkirk times. Though Elwood and his colleagues had yet no clues as to the operation’s target, it turned out to be the French resort town and port of Dieppe on the Channel coast. Among the principal planners of this so-called Reconnaissance in Force was Lord Louis Mountbatten, recently appointed Britain’s Chief of Combined Operations.

In late April, 1942, as planning progressed, units from the 2nd Canadian Division, Rileys included, were selected to take part in the venture. Described by a senior British general as “first class chaps”, they were in fine physical shape and supposedly “itching for action” after their long and often tedious training stint in England. The operation, code named “Rudder”, was ultimately approved by both British and Canadian officialdom at the highest level and scheduled to be set in motion in early July, 1942. The principal object was to cripple enemy defence installations, military stores, and the nearby airport. In other words, destroy and disrupt seemed to be the order of the day. The plan also called for the use of parachute troops and a massive preliminary aerial and naval bombardment of the target.

On May 17th, the RHLI’s adrenlin shot up when it was suddenly ordered to Portsmouth Harbour and put on ferries bound for Ryde on the Isle of Wight. From there they took the train to Newport and made camp at a site called Parkhurst Wood. The strict security and censorship imposed, which probably recruited Elwood’s knowhow, only added to the excitement and the tension. In surroundings resembling the Dieppe beachscape, the rank and file were instructed in hill-climbing, landing through smoke, street fighting, and speed marching. But the crucial prerequisite to all this was to get them to the objective in the first place. To that end Elwood and the other Riley officers led their men in time-consuming embarkation, disembarkation, and withdrawal exercises in newly designed landing craft. Two such exercises were required, Yukon 1 and 2, because on the first try the Royal Navy failed to land the amphibious trainees at the designated time and place.

The third exercise, Klondike, would, if all went well, be the real thing, the Channel crossing to the still undisclosed objective. Then on 27th June officers were at last let in on the secret and told of the target’s identity. A short time later, on the evening of Dominion Day, it was the rank and file’s turn to learn directly from their CO that Dieppe was indeed their destination. This certainty, however, soon proved illusory. The weather and the moon and the tides failed to play their essential role in the drama. As a result, Rudder was postponed, then put on hold, and finally, after much soul-searching in high places, cancelled altogether. The reactions to this decision were many and varied. There is no way of knowing of Elwood’s but he may have shared the frustration of others, that after all the time and energy spent on tediously preparing for action, that action had disappeared almost literally in a puff of smoke. The sudden drop in crisis-driven adrenalin among the affected must have been visible for all to see. Those who had long been itching for action were left itching and disgruntled. To others it may have brought a mixture of these emotions and a sense of relief, that for the time being at least they would not have to put their lives on the line.

That interval, however, had a short shelf life. Within days of Rudder’s cancellation, Mountbatten and fellow planners succeeded in resurrecting it under the new code name of Jubilee, in the optimistic belief that a successful operation could still be mounted before summer’s end. A favourably disposed Winston Churchill weighed in and for good reason. He had recently been obliged to inform an enraged and embattled Stalin that the Western Allies could not undertake anything like a full scale invasion of the Continent in 1942, that is, the Second Front the Soviet dictator was demanding. What the Prime Minister did pledge in the short term was an admittedly distant second best, a series of hopefully diversionary attacks on specific targets on the French coast. For Churchill, a substantial amphibious assault on Dieppe was made to order, politically as well as militarily.

Even so, Rudder was not totally restored. Because of logistical problems commandos were substituted for parachute troops and no arrangements were made this time around for a major softening up bombardment from air and sea. The latter adjustment was never made known to junior officers like Elwood, let alone to the rank and file. But many of them, brought up on tales of the Great War, would have taken for granted that a heavy bombardment of one kind or another would precede an infantry charge over open ground. In any case, to use modern phraseology, Jubilee’s planners feared too much collateral damage (French civilian casualties) if such a tactic were used at Dieppe. Another factor considered was that aerial bombing would create much rubble, an impediment to the movement of tanks. The issue was moot anyway. RAF Bomber Command, which had already inaugurated its own large scale war against German cities and industries, claimed that it lacked the ability to pinpoint and precisely attack the comparatively small targets at Dieppe. Again all of this back and forth remained securely locked up in the lofty stratosphere of high command. Meanwhile the revised plans that shaped Jubilee hurriedly went forward.

These included changes in the command structure that reflected the significant Canadian contribution to the effort. A presumably gratified Elwood learned that General H.G.D. Crerar, commander of the 1st Canadian Corps in Britain, was named Mountbatten’s virtual deputy, this at the urging of General A.G.L. McNaughton, Chief of the Canadian General Staff. Major General J.H. Roberts, commander of the 2nd Division, would provide further Canadian input by directing the landing from a ship off shore. Though the watchful Germans, armed with air reconnaissance intelligence, must have realized that something was in the works, the British did their best to mask the preparations for Jubilee, now scheduled for 19 August 1942. When the word was given, the raiding units would be sent directly to five different points of departure where they would quickly board the landing vessels that would make the hundred or so kilometer trip to the waters off Dieppe.

These included changes in the command structure that reflected the significant Canadian contribution to the effort. A presumably gratified Elwood learned that General H.G.D. Crerar, commander of the 1st Canadian Corps in Britain, was named Mountbatten’s virtual deputy, this at the urging of General A.G.L. McNaughton, Chief of the Canadian General Staff. Major General J.H. Roberts, commander of the 2nd Division, would provide further Canadian input by directing the landing from a ship off shore. Though the watchful Germans, armed with air reconnaissance intelligence, must have realized that something was in the works, the British did their best to mask the preparations for Jubilee, now scheduled for 19 August 1942. When the word was given, the raiding units would be sent directly to five different points of departure where they would quickly board the landing vessels that would make the hundred or so kilometer trip to the waters off Dieppe.

The word came for the Rileys early on August 18th, and by the afternoon 582 of them, including Elwood and thirty other officers, were trucked to Southampton, their designated port, and transferred to their so-called mother ship, the Glen Gyle. To help preserve the always precarious element of secrecy, the rank and file, who mistakenly thought they were on a practice exercise, were not told of their real mission until they were all safely on board. When the ship left Southampton that night officers remarked on the “eerie” quiet of apprehension as the men set about inspecting weapons, checking equipment, priming grenades, and examining the French currency they had been issued. As well, with the help of officers like Elwood they mentally rehearsed their recent training on the Isle of Wight.

The Glen Gyle duly joined a large destroyer- escorted flotilla that transported the rest of the raiding force. Including the RHLI, some 6100 men, of whom 4963 were Canadians, made their way across a comparatively unruffled Channel. The Rileys were accompanied by fellow regiments or units, namely the Essex Scottish, the Calgary Tanks, the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, the South Saskatchewan, and the Royal Regiment of Canada. They would all soon face their baptism of fire at the hands of a war-hardened and resourceful foe that had yet to lose a battle. Within eight miles of their target, the Glen Gyle, as planned, unloaded Elwood and its other passengers into landing craft that then headed for the enemy shore. The RHLI together with the Essex Scottish and the Calgary Tanks had been designated to lead the frontal assault.

The Canadians should have been landed in pre-dawn darkness but delays brought them ashore at approximately 4:45, just as the sun was starting its all-disclosing ascent on the horizon. From his vantage point in a landing craft (LCA), the RHLI’s Captain Denis Whitaker provided a compelling backdrop to the touchdown on the beach. He also unloaded his own strong sense of foreboding, which must have been shared by Elwood and other bewildered officers and men in the landing parties. Whitaker’s account is a modified replay of his resume of the raid written at the time and referred to in the regiment’s War Diary entry for 19 August 1942.

“… I could see”, he wrote, “the dim outline of the buildings along the Dieppe front.” He tersely continued:

We cruised on; the shore came into focus. … Something was terribly wrong. Everything was intact! We expected a town shattered by the RAF’s saturation bombing the previous night… There was no sign of bombing …. Smoke had been laid down to mask our approaches. Now through the wisps of smoke, I could see the rocky beach backed by the sea wall, the buildings and the hotels on the far side of the green esplanade, and the casino immediately ahead on the right. That was White Beach, my battalion’s objective. … What frightened me most was the way the headlands on both sides were wrapped around the beach. Enfilade fire from both flanks could make it a terrible killing ground.”

Sadly it proved to be so. As a dismayed Whitaker observed, unbeknownst to junior officers and the rank and file, no overwhelming air and naval bombardment had been laid on for reasons already stated. To be sure, there was a sweep of cannon-armed Hawker Hurricane squadrons over the Germans’ positions just before the Canadians disembarked. Almost simultaneously Royal Navy destroyers tried to do their share by shelling enemy strong points on the forbidding headlands. But neither action had long-lasting effects and the Germans recovered to blast away at beached and incoming landing craft alike.

Though dramatic, the air sweep’s brevity was bitterly lamented by the disappointed boots on the ground. Not only that, they were initially shorn of tank support because of faulty co-ordination efforts. As a result, Elwood and the others went into action virtually “naked” – the term used in a contemporary account – against regrouped enemy defenders, who, well armed with mortars and machine guns, reacted with their customary skill and determination. Even before the RAF’s intervention they had already been alerted by, among other signals, an exchange of gunfire when British destroyers had bumped into an unexpected enemy convoy.

Elwood was among the first to hit what Whitaker bluntly called the Beach of Hell. He and the hundred men in his command, the RHLI’s B Company, one of three companies involved, was assigned what turned out to be the fanciful task of taking the heavily defended casino, neutralizing nearby buildings, including a Gestapo headquarters, and knocking out enemy strong points elsewhere in the town. The plan and those devised for B Company’s sister units were soon brutally snuffed out. For his part, Elwood, after resolutely negotiating half the width of the tricky stone-studded White Beach, was cut down by the foe’s well placed machine guns. Ironically this Bisley marksman had had apparently no opportunity to discharge his own weapon during his scramble up the beach.

Elwood was among the first to hit what Whitaker bluntly called the Beach of Hell. He and the hundred men in his command, the RHLI’s B Company, one of three companies involved, was assigned what turned out to be the fanciful task of taking the heavily defended casino, neutralizing nearby buildings, including a Gestapo headquarters, and knocking out enemy strong points elsewhere in the town. The plan and those devised for B Company’s sister units were soon brutally snuffed out. For his part, Elwood, after resolutely negotiating half the width of the tricky stone-studded White Beach, was cut down by the foe’s well placed machine guns. Ironically this Bisley marksman had had apparently no opportunity to discharge his own weapon during his scramble up the beach.

His fate and that of B Company would be grimly typical of the operation’s wretched outcome. Though Whitaker and his men briefly retrieved the situation by blasting into the casino and killing, taking prisoner, or routing its German occupants, their intrepid action, like those of other units, left no lasting footprint. After several hours of dogged fighting, heavy losses, and maddening futility, those Rileys and the other Canadians who could, managed to extricate themselves and make their hazardous way back to England. Indeed their withdrawal was as horrendous as their arrival. The rescue vessels were under constant fire from shore and subjected to strafing and dive bombing from the air – a kind of mini-Dunkirk gone bad.

Overall the raid had been a gory tactical defeat. Of the some 5000 Canadians who had participated, more than half had to be left behind, the killed and the wounded and unwounded. The Rileys had suffered proportionately, if not more so. Only 217 out of a force of 582 made it back to England, and of these 115 were listed as wounded The rest of the force had no such luck, Among the unwounded who were captured, were the CO, Colonel Labatt, and the chaplain, Honorary Captain John Foote. Foote declined to be evacuated so that he could tend to the needs of the wounded and the dying, a selfless act that earned him the highest honour, the Victoria Cross.

Those survivors temporarily hospitalized for their wounds eventually join their manacled and shackled comrades in prisoner of war camps. The harsh treatment meted out to them was in retaliation for the binding of German prisoners during the hectic fighting in the casino, when the Rileys could spare no one to watch guard over them. In any case, both actions were violations of the Geneva Convention.

The imagined latter-day visitor to the Dieppe War Cemetery may not have noticed that the victors had buried and marked the Canadian dead in the German style, that is, with markers placed back-to-back in long double rows. In 1944 when Canadians military authorities returned to Dieppe in far different circumstances, they saw no reason to change the German burial arrangement.

As expected the outcome of the Dieppe Raid had a sombre impact on the City of Hamilton, the home of the stricken RHLI. At first trumpeted as a triumph, it all too soon became painfully apparent, as casualty lists appeared in the local newspaper, that something had gone woefully wrong with Jubilee. On 21 August 1942, for example, Elwood and other casualties were featured with portraits on the front page of the Hamilton Spectator. The whole city was plunged into mourning. Decades later the terrors that turned a French sea front into a “Beach of Hell” could still haunt a Riley survivor of the raid, just as they had haunted him when he again approached Dieppe in 1944, though this time from the landward side and in the vanguard of a liberating force.

As expected the outcome of the Dieppe Raid had a sombre impact on the City of Hamilton, the home of the stricken RHLI. At first trumpeted as a triumph, it all too soon became painfully apparent, as casualty lists appeared in the local newspaper, that something had gone woefully wrong with Jubilee. On 21 August 1942, for example, Elwood and other casualties were featured with portraits on the front page of the Hamilton Spectator. The whole city was plunged into mourning. Decades later the terrors that turned a French sea front into a “Beach of Hell” could still haunt a Riley survivor of the raid, just as they had haunted him when he again approached Dieppe in 1944, though this time from the landward side and in the vanguard of a liberating force.

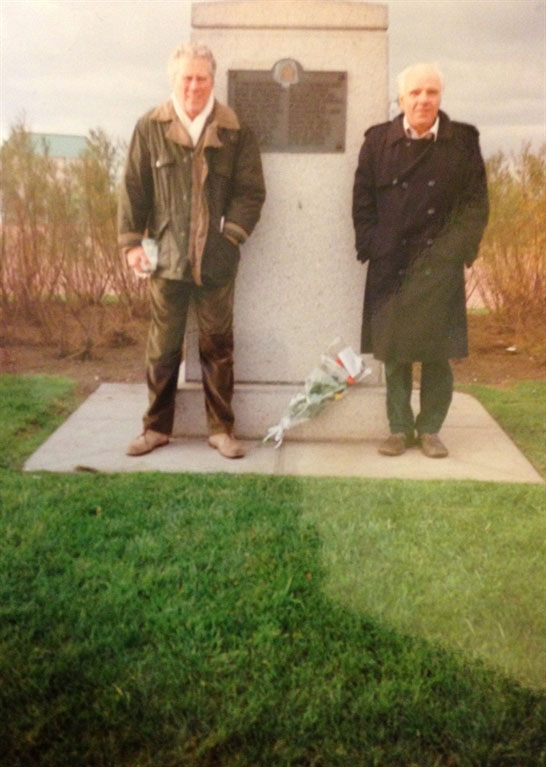

In 2008, a Dieppe Memorial, designed as a replica of White Beach complete with large stones, was constructed on a stretch of Burlington Beach. It serves as a bookend to the commemorative cairn overlooking the former battle scene at Dieppe.

C.M. Johnston & Lorna Johnston

Note: The picture of the Dieppe memorial cairn was taken in 1989. C.M. Johnston is standing on the left.

*********************************************

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Linda Payne, who kindly assisted with other Honour Roll biographies, researched invaluable Matchett family data and other documentation, including the Peterborough connection. Equally helpful on military matters was Tim Fletcher, who supplied, among other things, the Matchett image and a map. The following also provided key information: John Aikman (Educational Archives), Margaret Houghton (Hamilton Public Library), Adam McCulloch (Canadian Baptist Archives), and Sheila Turcon (McMaster University Library).

SOURCES: National Archives of Canada: Wartime Personnel Records, Record Group (RG) 24, Service Record of Captain George Elwood Matchett; War Diary of the 1st Battalion of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, 1 Aug. – 31Aug.1942; Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Commemorative Information on Captain George Elwood Matchett; McMaster University Library/Special Collections: Silhouette, 7 Nov. 1933; 13, 27 Nov. 1934, 5 Feb. 1935; Marmor 1934, p. 117, 1935, p. 129; McMaster Divinity College/Canadian Baptist Archives: Student File 4824, George Elwood Matchett, Biographical File, George Elwood Matchett; Archives of the Hamilton-Wentworth School Board: Attendance Records, Stinson Street School, Grades Sheet, Hamilton Collegiate Institute; Hamilton Public Library/Special Collections and Local History: Matchett File, Vox Lycei, Xmas 1924, pp. 41, 42, Christmas 1926, pp. 25,26, 28, Xmas 1927, pp. 52-54, 55-59, Xmas 1928, p. 60; Hamilton Spectator, 14 Aug., 9 Oct. 1937, 21 Aug. 1942, Montreal Gazette, 31 July 1937, Globe.15 Aug. 1937.

Books and studies abound on the Dieppe Raid, among them, the absorbing ones quarried for this biography: Denis Whitaker, Dieppe: Tragedy to Triumph (Toronto and Montreal: McGraw Hill-Ryerson, 1992), especially Chapters 17-19; Jacques Mordal, Dieppe: The Dawn of Decision translated by Mervyn Savill (London: New English Library Limited/Times Mirror, 1981), T. Murray Hunter, Canada at Dieppe, with a foreword by C.P. Stacey (Ottawa: Canadian War Museum, Historical Publication No. 17, 1982).

Other essential works include Kingsley Brown, Sr.(1862-1942). Kingsley Brown, Jr.(1942-1945) and Brereton Greenhous (1945-1977), revised and edited by Brereton Greenhous, Semper Paratus: The History of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (Wentworth Regiment), 1862-1977 (Hamilton: W.L. Griffin Ltd. 1977), Chapter 13; C.P. Stacey, The Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War, Volume 1: Six Years of War: The Army in Canada, Britain, and the Pacific (Ottawa, Queen’s Printer 1955), Chapter XI, especially pp. 374-5.