Dr. C.M. Johnston's Project

Discover McMaster's World War II Honour Roll

William D. W. Hilton

The Bristol Beaufighter, flown in Britain all too briefly by Flight Lieutenant William (Bill) Hilton, was a close relative of the Bristol Beaufort torpedo bomber, the kind navigated in Egypt by another McMaster Honour Roll airman, Pilot Officer Thomas O'Neil, who, like Bill, served also as a “one tripper” with RAF Ferry Command. The Beaufighter, a high speed twin engined, long range attack weapon, came powerfully armed with 20 mm. cannons in the nose and a battery of machine guns in the wings.The aircraft was conceived on the eve of the war's outbreak in 1939, that is, just before Bill began thinking of enlisting in the RCAF. He may have learned later that the machine was designed to counter the Lufwaffe's new twin-engined Messerschmitt 110, ominously dubbed “The Destroyer”. The freshly minted Beaufighter became operational in October 1940, but unfortunately not in time for the Battle of Britain. That large scale aerial engagement had been fought to a crescendo just weeks before and won, though narrowly, by RAF Fighter Command, a dramatic turn of events that forestalled a threatened German invasion of the British Isles.

Bill Hilton, who in time came to handle the controls of the comparatively new Beaufighter, was born in Chicago, Illinois on 17 May 1916, that is, according to information entered later on his RCAF service record. His McMaster admissions application says otherwise, however, that his birthplace was St. Cartharines, Ontario though a search of the local newspaper, the Standard, uncovered no birth announcement for the date in question. In the interval between McMaster and the RCAF Bill may have been advised of the true state of affairs. In any case, it is unlikely that he would provide false information to the military.

The Chicago birthplace is plausible enough given that Bill's father, D'Arcy Hilton, was an American businessman - described as “flashy” by a contemporary -who apparently served in the Great War as a pilot with the fledging US Army Flying Corps. Bill's mother, Gladys (Woodruff) Hilton, had met her future husband, a then oarsman with the Detroit Rowing Club, when he participated in one of the pre-war Henley Regattas in her home town of f St. Catrtharines, where the couple were ultimately married on 28 January 1914. Gladys's background could not have differed more markedly from her husband's. She came from United Empire Loyalist stock and her prominent family had long been settled in the Niagara peninsula, one of several British-controlled regions that had served as a haven for those fleeing the American Revolution.

According to family accounts, less than two years after Bill's birth, the Hiltons were divorced, a then comparatively rare and costly procedure that was readily financed by Gladys' obviously concerned father. By this time she had left Chicago for St. Catharines with son Bill in tow. She shortly had him baptized in the family's place of worship, the city's venerable St. George's Anglican Church, which dated from the late 18 th century. Several years passed and Gladys married again, this time Dr. William James Chapman, reputedly a “well respected and colourful” physician, who for years drove about the city in a large and distinctive Pierce-Arrow motor car. The wedding ceremony took place on 4 August 1925 at the home of the bride's pleased parents. In his reconstituted family Bill, who retained his original surname, dutifully worshipped at St. George's in the company of the Chapmans.

As for his schooling, hitherto provided by the public system, the comfortably off family enrolled him in 1925 at Ridley College, a local private school, whose solid academic reputation and Anglican credentials readily recommended it. In its extracurricular department Bill excelled at football and played on Ridley's championship team in 1933. As fondly recalled by his half brother, Alfred Chapman, he was easily identifiable by the number 12 on his jersey. Also on hand to applaud Bill's exploits was his supportive stepfather, who, as the college physician, would have been there in any case to care for possible injuries on the gridiron.

Like another future McMaster airman, Harry Zavadowsky, Bill also went out enthusiastically for boxing. The sport was then a popular attraction not only at his school but in the male community at large that eagerly followed the exploits of the leading pugilists of the day, most notably the celebrated “Brown Bomber'”, Joe Louis, who long reigned as the world heavyweight champion. Meanwhile in the smaller world of the Ridley ring Bill was making his own mark. He was judged a boxing finalist in 1932 and declared “best boxer” three years later, the same year that he was also starring on the gridiron. At Ridley Bill also formed a close friendship with fellow footballer and classmate, Frederick Edgar (Ed) Wellington [HR], who would later join him in the Air Force and similarly serve as a flight instructor.

After graduating from Ridley in 1936, Bill ventured into higher education at the University of Western Ontario where his stepfather hoped that that he would follow in his footsteps and train to become a doctor. In London Bill was duly enrolled in Western's medical school but after spending just two year there he dashed his stepfather's hopes by announcing that medicine was not for him. At this point he left London for Hamilton and another stint of higher education at McMaster University, again with parental approval and support. During his brief stay at Western Bill had gone out for his favorite sport, football, playing in the backfield of the Western Colts, the school's intermediate intercollegiate squad. According to the student yearbook, Occidental, he also opted for a new and challenging diversion by joining the school's fencing team.

On 26 September 1938, the day that Bill applied to enter McMaster, the foreboding Munich crisis was threatening to plunge the world into another war. Though it was shortly defused, an uneasy peace followed and proved a mere prelude to the war that would ultimately decide Bill's fate. Like so many other Canadians, he may well have paid heed to such headline-generating developments but for the moment he concentrated as best he could on completing the paperwork for his admission and registration at McMaster. A former Toronto institution founded under Baptist auspices, it was then marking its ninth year on its spacious Westdale campus. Besides cultivating its immediate Hamilton constituency, it was also seeking to build up a modest hinterland in the Niagara peninsula, including the St. Catharines area, which Bill still called home. He proceeded to register in the popular Course 9, Political Economy (Economics) Option, with a view to pursuing a career in “business”, a brave choice given the sour economic climate of the Depression ‘thirties. In any case, he was apparently given credit for the work he had completed at Western for he was admitted to the second year program of Course 9.

Bill also sought and obtained a place in the redbrick residence, Edwards Hall, and subsequently ended up in its North House, reputedly the most raucous in the building. His stay there was highlighted by the presence of his roommate, Ed Wellington, his old friend from Ridley College days. In Edwards Hall they may also have crossed paths with other future servicemen and Honour Roll candidates, among them, Nairn Boyd and Gordon Holder. By the time they all took their first week of classes they had learned that the war the Munich crisis had threatened to bring on had been thankfully (if only temporarily) averted.

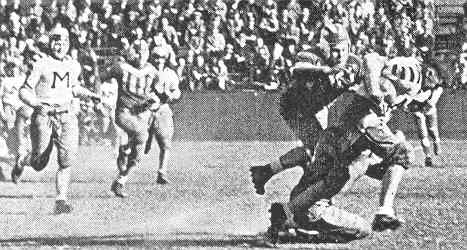

In his time at McMaster Bill, as he had at Ridley College and Western, entered onto a variety of sports, going out primarily for football though also participating in track and fencing, the diversion he had sampled in London. Standing over 5'8” and weighing some 150 pounds, the speedy freshman played on the McMaster Maroons football team as flying wing and placement kicker. He was also adept at the fine art of dropkicking while backfield play was in motion. As well, he shone as a pass receiver, as noted by the Marmor, which also carried a photograph of one particular play, captioned: “Hilton is being pulled down after taking a short forward pass to gain a good eight yards”.

In his time at McMaster Bill, as he had at Ridley College and Western, entered onto a variety of sports, going out primarily for football though also participating in track and fencing, the diversion he had sampled in London. Standing over 5'8” and weighing some 150 pounds, the speedy freshman played on the McMaster Maroons football team as flying wing and placement kicker. He was also adept at the fine art of dropkicking while backfield play was in motion. As well, he shone as a pass receiver, as noted by the Marmor, which also carried a photograph of one particular play, captioned: “Hilton is being pulled down after taking a short forward pass to gain a good eight yards”.

Such exploits in the 1938 season did not prevail, however, in one of the games against Bill's former team, the Western Colts. The stung Maroons subsequently regrouped, however, to defeat Varsity's intermediate squad, a victory nailed down by Bill's two field goals, one from twenty yards out. After most games, some of which were played at Hamilton's HAAA Grounds, the weekly Silhouette reported that he also provided solid backup and blocking for the talented Charlie Szumlinski, the plunging back, who like his supportive teammate later served with the RCAF.

Bill's efforts on the gridiron and his proficiency in fencing and track made him a McMaster Colour winner, 2nd grade, the same athletic award won by Henry (Hank) Novak, another keen footballer and future airman. Bill appeared to lead a full social life on campus as well, as yearbook pictures of student functions make plain. A picture taken at the Wallingford Hall Formal, for example, is simply but revealingly captioned, “Blase: Hilton and partner”. Both were clearly at home doing the “light fantastic”.

Meanwhile Bill was trying to tackle his classroom work load. Always more at home with athletics than with the things academic, Bill suffered an adverse mixture of failures and passes and was obliged to withdraw from the regular Course 9 programs and become what was known as a Partial Student. The decision, not entirely unexpected, was handed down in the summer of 1939, before the start of the new academic session. Though his service record hints at his having subsequently taken correspondence courses there is nothing indicating that in the McMaster documentation. It turned out to be strictly academic in every sense of the term anyway because after the outbreak o war in September, 1939 Bill appears to have put the lecture hall and a business future out of mind and concentrated instead on possible service with the RCAF, as did many of his close fiends, including former Edwards Hall roommate, Ed Wellington.

Meanwhile Bill was trying to tackle his classroom work load. Always more at home with athletics than with the things academic, Bill suffered an adverse mixture of failures and passes and was obliged to withdraw from the regular Course 9 programs and become what was known as a Partial Student. The decision, not entirely unexpected, was handed down in the summer of 1939, before the start of the new academic session. Though his service record hints at his having subsequently taken correspondence courses there is nothing indicating that in the McMaster documentation. It turned out to be strictly academic in every sense of the term anyway because after the outbreak o war in September, 1939 Bill appears to have put the lecture hall and a business future out of mind and concentrated instead on possible service with the RCAF, as did many of his close fiends, including former Edwards Hall roommate, Ed Wellington.

Family lore has it that Bill and Ed signed up the day after British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain made his gloomy radio speech announcing that war had been declared against Germany because she had given no “undertaking” to withdraw her invading troops from Poland. If Bill and his friend did in fact try to enlist this early on they would have been turned back simply because the RCAF was not actively recruiting in these opening weeks of the war. As it turned out, Ed Wellington did not formally enlist until July, 1940, some ten months after Canada followed Britain's lead and entered the war. As for Bill's signing up, his RCAF service record does not carry the usual enlistment entry but rather his appointment as a PO (Pilot Officer) on 29 January 1940. Where or how he might have put in any service time before that appointment was made, is not made clear in the documentation,

Because it was the war's early days and comparatively few recruits were in the pipeline, perhaps a candidate who displayed a lively and self-assured demeanour along with qualities that made him stand out as a potential leader may have been among the reasons for this ostensibly premature appointment. Bill indeed may well have shown the flair and the presence often attributed to his biological father. And the fact that D'Arcy Hilton had seen service as an airman in the Great War may have also have had some bearing on the situation. Further, Bill's family and educational background of Loyalist heritage and private school and university may also have been taken into account by those who made the decisions on these matters.

It is worth noting too that he was given a serial number prefixed with “C”, which indicated that he was in fact allocated to permanent force personnel, that is, those planning to go beyond wartime service and actually make the Air Force a career, a decision that Bill apparently took. In any case, this may explain why, after being elevated to Pilot Officer, Bill was immediately dispatched to the Western Air Command Headquarters, recently transferred to Victoria. British Columbia as a means of establishing better co-ordination with Canadian Army and Navy commands on the Pacific coast.

When Bill arrived on the scene the installation had been functioning for some two months at Pat Bay, now the site of the Victoria International Airport. His stay at Pat Bay was short, however. His assigned duties there are unknown though they probably involved an administrative job of some sort. Given his lively personality, background, and motivation, he doubtless preferred the active life of flying to being deskbound. In any event, the upshot was his departure in mid-March for the Winnipeg Flying Club, one of the private facilities pressed into the wartime service of instructing pilots. He did no training there himself but he did sign the RCAF service roll, the procedure that would pave the way for his formal flight instruction.

The first stage of it unfolded after mid-April at the recently established No. 1 Initial Training School (ITS) located in Toronto in the spacious buildings of the Canadian National Exhibition, most notably the distinctive “Cow Palace”. After submitting to varied physical, aptitude, and psychological tests, he was pronounced fit to undertake pilot training, first, at RCAF Trenton and then at Camp Borden, the permanent peacetime establishments. In the early days of the war these were the only installations available since the stations to be established under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, set in motion in late 1939, were not yet up and running.

At Trenton, where Bill arrived on 17 th May – his 24 th birthday -- he took his elementary instruction in, among others, the Fleet Finch aircraft, one of the standbys of Training Command. With the perceived flair his father had shown in an earlier war he successfully met all the requirements, as his proud family expected he would. A short month after his arrival at Trenton he moved on to the next stage at Camp Borden, a form of advanced instruction later known as Service Flying Training.

It was during this exciting time that Bill became engaged to Errol Grosch, the daughter of Henry Grosch, a county court judge in Chatham, who would later preside over a controversial ethnic discrimination case. Errol and Bill had known one another for years as close neighbours on Lake Joseph in the so-called posh area of the Muskokas, where their families enjoyed cottage retreats. Initially they had taken accommodations at the local resort hotel, the Belmont House, where Bill would later escort Errol to dances and parties. The Lake Joseph cottage was a retreat in every sense for Dr. Chapman, who refused to have a telephone on the premises for fear it would mean the house calls that claimed so much of his time in St. Catharines. His son, Alfred, also enjoyed the experience, fondly recalling, among other things, how his patient half brother taught him to swim.

In the academic session1939-40 Errol was completing her final year at the University of Toronto and saw Bill in the city as frequently as his duties permitted. Samuel (Sam) Woodruff, Bill's admiring and respectful young cousin, recalled the time when his “idol” and Errol took him on their Toronto movie date to see “Captains of the Clouds”, one of the many patriotic films churned out during the war. On 3 rd August, while Bill was in the last stage of his flight training, he and Errol , the freshly minted university graduate, were married as planned. The ceremony took place in the United Church in the village of Stroud, with the groom on a short leave from nearby Borden in full uniform and both families in attendance. After the newlyweds enjoyed a brief honeymoon, Bill returned to Borden and on 19 th August received his wings at a ceremony, which, like the wedding, was attended by a full representation of the Chapman and Grosch families.

Now armed with his pilot's badge Bill was assigned to an advanced flying program, better to prepare him for the assignment that would transform him from trainee to trainer. On 5 th October he completed the assignment with a grade of 70% and was then almost immediately dispatched to a flying instructors' course. Clearly the need was seen at this time to build up a cadre of instructors to train those already streaming in under the BCATP. This was not from all accounts Bill's first choice – he would have preferred active service overseas to training others – but he was obliged to do what he was told.

At Borden for the better part of a year and a half he instructed new recruits in aerial fundamentals in, among others, the twin-engined Avro Anson and Airspeed Oxford, as well as in the by now familiar Harvard. In early 1942, to buttress his skills he was put through another course of instruction, which he completed with a “B” standing, a full grade above that achieved on the first course he had taken. In short order, on 16 February 1942 he was promoted from Flying Officer, a rank he had attained in October, 1940, to Acting Flight Lieutenant, a gratifying elevation for this 26-year old “captain of the clouds”.

During his stint as an instructor at Borden the zestful Bill sometimes broke with routine. On one memorable occasion he provided a genuine treat for the worshipful Sam Woodruff and a severe shock to his mother's nervous system by flying his Harvard very low over Lake Joseph and noisily “buzzing” the startled cottagers, who could clearly see his beaming face in the cockpit. On another occasion he apparently favoured his old school, Ridley College, with a similar performance, much to the annoyance of the headmaster, who never learned the identity of the gleeful culprit.

By all accounts, Bill eventually began to chafe at the instructor's job and seek a posting overseas. His wish was finally granted on 14 th April when, like Tom O'Neil, he was assigned to RAF Ferry Command, the organization that shuttled aircraft to Britain over the so-called “Ocean Bridge” tenuously spanning the North Atlantic. The plan, recommended by a far sighted RCAF commander in April, 1940, was inaugurated three months later, following the enemy's shockingly successful Blitzkrieg in Western Europe, soured on by a powerful Luftwaffe.

On Bill's last leave home before departing for his Ferry Command duties and service overseas, Dr. Chapman thoughtfully suggested that he spare some time from Errol and the family to say his goodbyes as well to his natural father, D'Arcy Hilton, who, according to family accounts, was then living in Lewiston, New York. Bill apparently acted on the suggestion but what passed between father and son on that potentially poignant occasion is unknown.

Following this re-union and a few more days with Erroll and the Chapmans, Bill's next stop was at Dorval, outside Montreal, a station speedily formed just seven months before as a replacement for the overburdened one at St. Hubert. It was designed to serve as the new western terminus of Ferry Command's growing transatlantic operations. At the same time another station had materialized at the next stop, Gander, Newfoundland where the earmarked aircraft would actually take off on their transatlantic flights. The Gander Airport had been completed just before the war and by 1940 the RCAF was using it for the war against enemy U-boats. The largest airport in North America, Gander lay athwart the so-called great circle route between the Atlantic seaboard and Europe and, moreover, was close enough to Britain to allow aircraft to fly there without refueling. These were vital factors that made Gander so strategically ideal for Ferry Command operations.

Meanwhile, as Bill soon discovered, Dorval for its part had acquired, among other features, a ferry training school, a radio communications centre that put it in constant touch with the eastern ferry terminus at Prestwick, Scotland, and an extensive maintenance facility manned by technicians and mechanics who ensured that the aircraft destined to take the “Ocean Bridge” were fully up to the challenge. Bill was soon enough introduced to the workings of the ferry training school, where, if his service record is any guide, he was familiarized with the aircraft he would fly to Prestwick, the Lockheed Hudson, the same species successfully navigated by Tom O'Neil on a similar operation.

On 18 th May, with his Hudson indoctrination under his belt, Bill flew to Gander and awaited his turn to take off for Britain. That time arrived on the evening of the next day and posed a challenge that was a far cry from his days as a flight instructor, even if he was to be a “one tripper” only. that is, a flyer who deposited his ferried aircraft at Prestwick and then proceeded to other unrelated duties. Although well aware that others, including Tom O'Neil, had preceded him he must have been struck by the marked novelty of piloting an aircraft across the forbidding expanse of the Atlantic Ocean. Bill may have reminded himself that the pioneering British fliers, Alcock and Brown, had over twenty years before also taken off from Newfoundland on their historic Atlantic flight.

Bill and the three-man crew assigned him may have been among those who briefly had to join a queue at Gander because of bad weather conditions or he might have been cleared for take off almost at once. In either case, Bill and his crew had learned of the potential hazards lying in wait, among them, engine trouble, loss of oxygen, and a possible enemy intervention while en route to their destination. Tension must have competed with excitement therefore when on the evening of the 19 th , Bill was cleared to lift the Hudson off one off the massive Gander runways and gain the altitude prescribed for the journey. But that was the only prescription apparently. At this time there was virtually no form of traffic control as such and it was more or less left up to Bill and his navigator to set and maintain the best possible course. During the flight, which would typically take up some dozen hours, Bill and his crew had ample time between periodic checkups of their aircraft to talk, joke, and comment on whatever they observed, particularly when they eventually passed over Ireland, their first sight of land since leaving Gander. The excitement must have mounted at this point.

In due course, to everyone's joy and relief, the flight was successfully completed and Bill set the Hudson down at the Prestwick terminus. The “disemplaning” – the service term -- was followed by a de-briefing and a period of rest and relaxation, during which Bill doubtless dispatched a wire informing the Chapmans of his safe landing overseas. The day after his arrival at Prestwick, the 21 st May, Bill was on a southbound train heading for the Personnel Reception Centre at Bournemouth on the Channel Coast, which served as an antechamber to the training and operational structures to which overseas newcomers would eventually be allocated.

Bill spent nearly a month in Bournemouth, for the most part cooling his heels after a few days of submitting to medical examinations, lectures, and orientation programs, with part of the time probably spent doing odd jobs about the place. Then on 16 th June he was finally given his marching orders and armed with the flying kit and battle gear issued at Bournemouth he took a train north to Bedfordshire and the RAF Fighter Command station quaintly named Twinwood Farm, then home of No. 51 Operational Training Unit (O T U). As its name suggests, the station had been established earlier in the war on a wide, woods-flanked expanse of converted farm land a few miles from Bedford, the county seat. Bill's destination, 51 OTU, a Fighter Command unit, had taken up residence there barely two months before he put in his appearance.

Twinwood Farm later became widely known as the station from which Glenn Miller, prewar band leader turned US Amy Orchestra director, took off on his last ill fated flight. Bill in his peacetime existence would in all likelihood have danced at Western and McMaster social functions to such popular Miller compositions as “Tuxedo Junction”, “Moonlight Serenade”, and above all, “In the Mood”, which virtually became an Allied signature tune during the war.

Bill spent a month in the rural environs of Twinwood Farm, during which he may have flown, among other aircraft quartered at the station, a Hudson similar to the one he had ferried across the Atlantic. What is more certain is that by this stage of his Air Force career, given all his months as a flight instructor in Canada along with his other flying duties, he had amassed an impressive total of 1200 flying hours, which must have put him amongst the most qualified and tested pilots in the UK. All this may have played a part in his promotion on 1 st July from the acting rank to the confirmed rank of Flight Lieutenant. Two weeks later, having presumably completed everything required of him, he was ordered to depart 51 OTU and proceed to Acklington in Northumberland, the home of 406 Squadron. This operational unit had been established in May, 1941 as the RCAF's first nightfighter squadron and it bore the accurate though chilling motto, “We Kill by Night”. Bill may well have been told that its first “kill” had been recorded the following September when one of its Beaufighters downed a Junkers JU-88.

On the face of it, it would appear that Bill had been cleared to participate in actual operations with a seasoned unit but that did not happen. Barley five days after his arrival at Acklington, some of the time spent swapping tales with his compatriots, he was on the move again, this time to yet another OTU, No. 54, based just across the Scottish border at Charterhall in Berwickshire. This OTU had been formed in 1940 at Church Fenton in Yorkshire as part of the fighter defence of the heavily industrialized Midlands during the Battle of Britain and the subsequent “Blitz”. In its new locale in southeastern Scotland close to the ancient and castled county town of Duns, it was still functioning as a nightfighter station and housing its crews in that staple airfield accommodation, drafty Nissen huts.

Charterhall, in the informative words of another Canadian who served there, was

on level ground adjacent to the River Tweed … the boundary between England and Scotland …. From the runways, the ground rose gently and the station buildings were on this slope. At the top of the slope the station boundary was marked by a black topped road …. [A[ group of … Nissen huts … were located on the south side of this road. From here the terrain began a steeper slope toward Duns and into the Berwickshire hills. …

The Canadian veteran went on to note that while the Tweed formed the base of the airfield the nearby town Duns lay at its apex. He also wryly remarked in his helpful and self-effacing recollection that trying to do full justice to the airfield's dimensions and configuration was tantamount to someone “keeping his hands in his pockets while describing a spiral staircase”.

As for its weaponry, Charterhall came equipped with a variety of aircraft pressed into service as trainers or nightfighters, among them, the Bristol Blenheim, the Vickers Wellington, the Mosquito the “Mossie”), the so called “Wooden Wonder”, and not least the Beaufighter. Indeed, according to an official report, Bill was sent to Charterhall expressly “for conversion to the Beaufighter”, largely on the strength of his wide experience with twin-engined aircraft.

In his first few days at Charterhall Bill did no flying and on his off-duty hours he may have ventured into Duns and inspect its storied castle and the distinctive Mercat Cross, which signified the town's status as a market centre. If he did manage to do some sightseeing, that diversion and his ground duties came to an end on Wednesday, 23 rd July. What followed was later described in an RAF accident investigation report submitted at Charterhall. It noted that at mid- morning on the 23 rd , Bill was instructed to take his first flight in a Beaufighter. After boarding the aircraft, which had routinely been certified airworthy, he was taken aloft by a flight instructor who on a series of takeoffs and landings acquainted him with the controls and the landing procedure. Bill, already a highly experienced pilot, must have responded well to the instruction because he was immediately permitted to undertake solo practice flights but, to be sure, only in the in the close vicinity of the airfield because of approaching bad weather in the area.

Accordingly Bill confidently took off on his own, completed a circuit about the airfield and landed without a hitch. He then took off on a second solo flight but unaccountably, in what was deemed an “error of judgment”, he ventured off course, that is, beyond the prescribed circuit, and soon found himself in the thick of the worsening weather, marked by a drizzle and haze that sharply reduced visibility. He radioed his situation to the station control tower and was instructed to climb from his reported altitude of 1000 feet (“Angel 1”) to a safer one of 3000 (“Angel 3”) and to prepare to be electronically “homed' into the station.

For reasons unknown Bill, who appeared to receive the instruction, did not or could not heed it and thus failed to bring the Beaufighter up to the recommended Angel 3. Meanwhile an off-duty station officer who happened to be at his home in Duns, heard an aircraft overhead flying in circles as if its pilot had lost his bearings in the haze and drizzle. A short time later a farmer in the immediate area reported seeing a low-flying aircraft with its landing gear retracted doing a shallow dive and then leveling out. The next thing he heard was a crash and a sickening explosion. It was Bill's ill-starred Beaufighter slamming into the ground at high speed.

Unable to discern the lay of the land rushing up at him, Bill had been flying too low for his own good. He first of all struck a hedge, tearing off the Beaufighter's tail assembly. The maimed aircraft then continued on its way for some fifty yards before crashing, exploding, and burning, the ominous sounds heard by the farmer. Bill suffered multiple head and internal injuries, so massive that a medical officer who shortly arrived on the scene plausibly concluded that the victim of the accident had died instantaneously on impact.

As for the possible cause or causes of the crash the station's commanding officer who presided over the accident investigation satisfied himself on one crucial point. In his final report he answered “No” to the question: “Was the injury due to his fault, i.e. did it arise from negligence or misconduct or any blameworthy cause within his own control? “ And there the matter officially came to rest on 27 July 1942. Bill's fate closely paralleled that of fellow Honour Roll airmen Bud Heimrich, Jack Yost, and Harry Zavadowsky.

Within a year of Bill's death, his grieving mother and stepfather, as a means of memorializing him, commissioned and had installed an elaborate and dominating wooden screen, complete with commemorative carvings, on the rear wall of St. George's Church, the family's place of worship. The honour of unveiling the screen fell to Alfred Chapman, Bill's half brother. Meanwhile the McMaster Alumni News had already paid its own tribute to Bill as well as to his friend and former Edwards Hall roommate, Ed Wellington [HR], in the firm of a “Salute” in its issue of 15 October 1942.

William D/W. Hilton is buried in Duns Cemetery, Duns, Berwickshire, Scotland.

C.M. Johnston

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The following made important and varied contributions to this biography: David Adlam, Donald Brown, Sheila Brown, Jennifer Cawood-Fleury, Alfred Chapman, James Cross, Spencer Dunmore, Sandra Enscat, Jack Evans, Glen Hall, Lorna Johnston, Paul Lewis, Theresa Regnier, Melissa Richer, Garnet Smith, Carl Spadoni, Jean Wellington, Martha Wellington, and Samuel Woodruff. Sam Woodruff (cousin) was a mine of family information, providing vital details and pictures that illuminated the biography. Alfred Chapman (half brother) also supplied helpful family anecdotal data and illustrative material. David Adlam provided the welcome description of the Charterhall station in Scotland. Paul Lewis, Ridley College's Archivist, was good enough to produce information drawn from the school student publication, Acta Ridleana, and other sources. Sandra Enscat of the St. Catharines Public Library furnished key references from the St. Catharines Standard. Theresa Regnier of the D.B. Weldon Library of the University of Western Ontario provided the information from Occidental.

SOURCES: National Archives of Canada: Wartime Personnel Records / Service Record of Flight Lieutenant William D, W, Hilton, with accompanying RAF Accident Investigation Report, 27 July 1942; Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Commemorative Information on F/L William D.W. Hilton; St. Catharines Standard, 29 Jan. 1914, 4 Aug. 1925; Canadian Baptist Archives / McMaster Divinity College: McMaster University Student File 6815, William D.W. Hilton, Biographical File, William. D.W. Hilton, contains newspaper clipping ( Air Force Casualties ) and McMaster admissions application; McMaster University Library / Special Collections: Marmor, 1938-39, 60, 83, [92], 111; Silhouette, 20, 27 Oct. 3 Nov. 1938;, McMaster Alumni News , 15 Oct. 1942; Spencer Dunmore, Wings for Victory: The Remarkable Story of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan in Canada (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1996), 12, 56, 70-1; Carl A. Christie, Ocean Bridge: The History of RAF Ferry Command (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997, repr.), 19, 32-3, 131-3 and chap. 8 (“One Trippers”).

Internet:

www.controltowers.co.uk/T-V/Twinwood_Farm.htm; www.shearwateraviationmuseum.ns.ca/squadrons/406sqn.htm (“No. 406 (HT) Squadron, RCAF”); www.raf-acklington.co.uk/Canadians.htm (“Canadians at Acklington”); www.rafcommands.com/_Fighter/54 OTUF.html ;

www.duns.bordernet.co.uk/history/ (“History of Duns”).